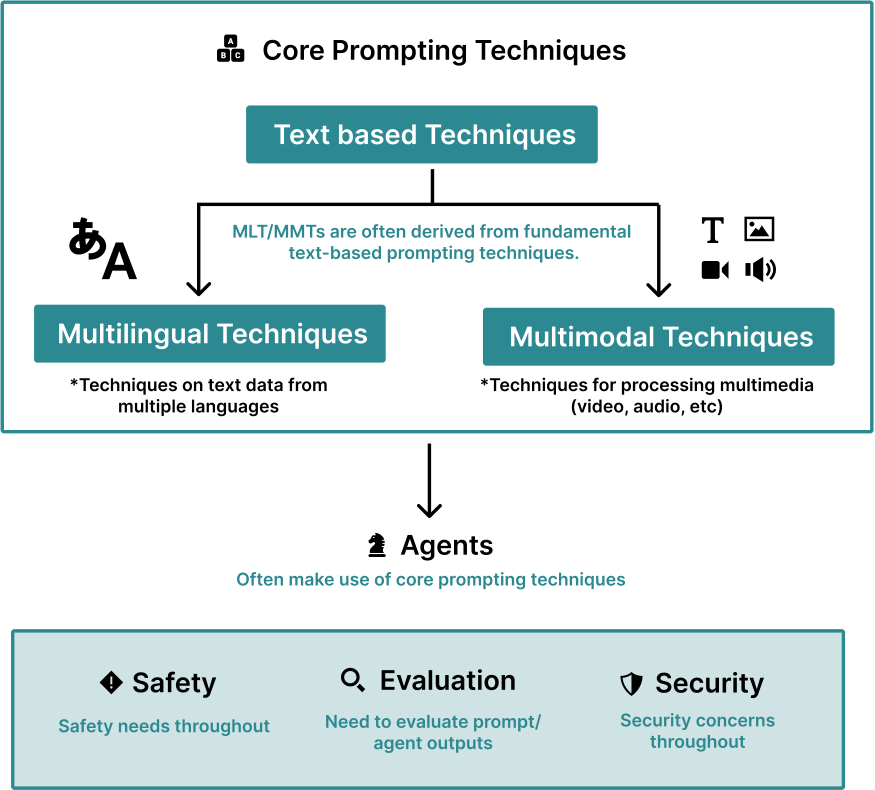

Transformer-based LLMs are widely deployed in consumer-facing, internal, and research settings (Bommasani et al., 2021). Typically, these models rely on the user providing an input “prompt” to which the model produces an output in response. Such prompts may be textual—“Write a poem about trees.”—or take other forms: images, audio, videos, or a combination thereof. The ability to prompt models, particularly prompting with natural language, makes them easy to interact with and use flexibly across a wide range of use cases.

Knowing how to effectively structure, evaluate, and perform other tasks with prompts is essential to using these models. Empirically, better prompts lead to improved results across a wide range of tasks (Wei et al., 2022b; Liu et al., 2023b; Schul- hoff, 2022). A large body of literature has grown around the use of prompting to improve results and the number of prompting techniques is rapidly increasing.

However, as prompting is an emerging field, the use of prompts continues to be poorly understood, with only a fraction of existing terminologies and techniques being well-known among practitioners. We perform a large-scale review of prompting techniques to create a robust resource of terminology and techniques in the field. We expect this to be the first iteration of terminologies that will develop over time. We maintain an up-to-date list of terms and techniques at LearnPrompting.org.

Scope of Study We create a broad directory of prompting techniques, that can be quickly understood and easily implemented for rapid experimentation by developers and researchers. To this end, we limit our study to focus on prefix prompts (Shin et al., 2020a) rather than cloze prompts (Petroni et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2021), because modern LLM transformer architectures widely employ pre-fix prompts and provide robust support for both developers and researchers (Brown et al., 2020; Google, 2023; Touvron et al., 2023). Additionally, we refined our focus to hard (discrete) prompts rather than soft (continuous) prompts and leave out papers that make use of techniques using gradient-based updates (i.e. fine-tuning). Hard prompts contain only tokens (vectors) that correspond to words

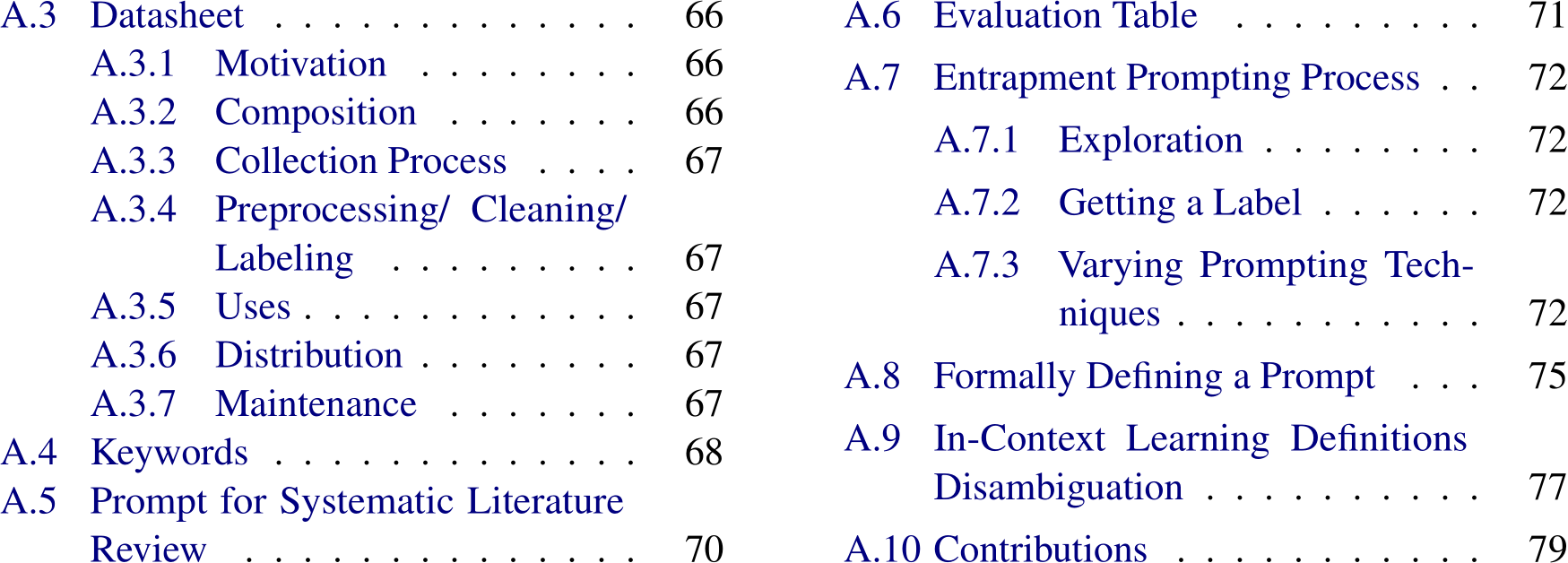

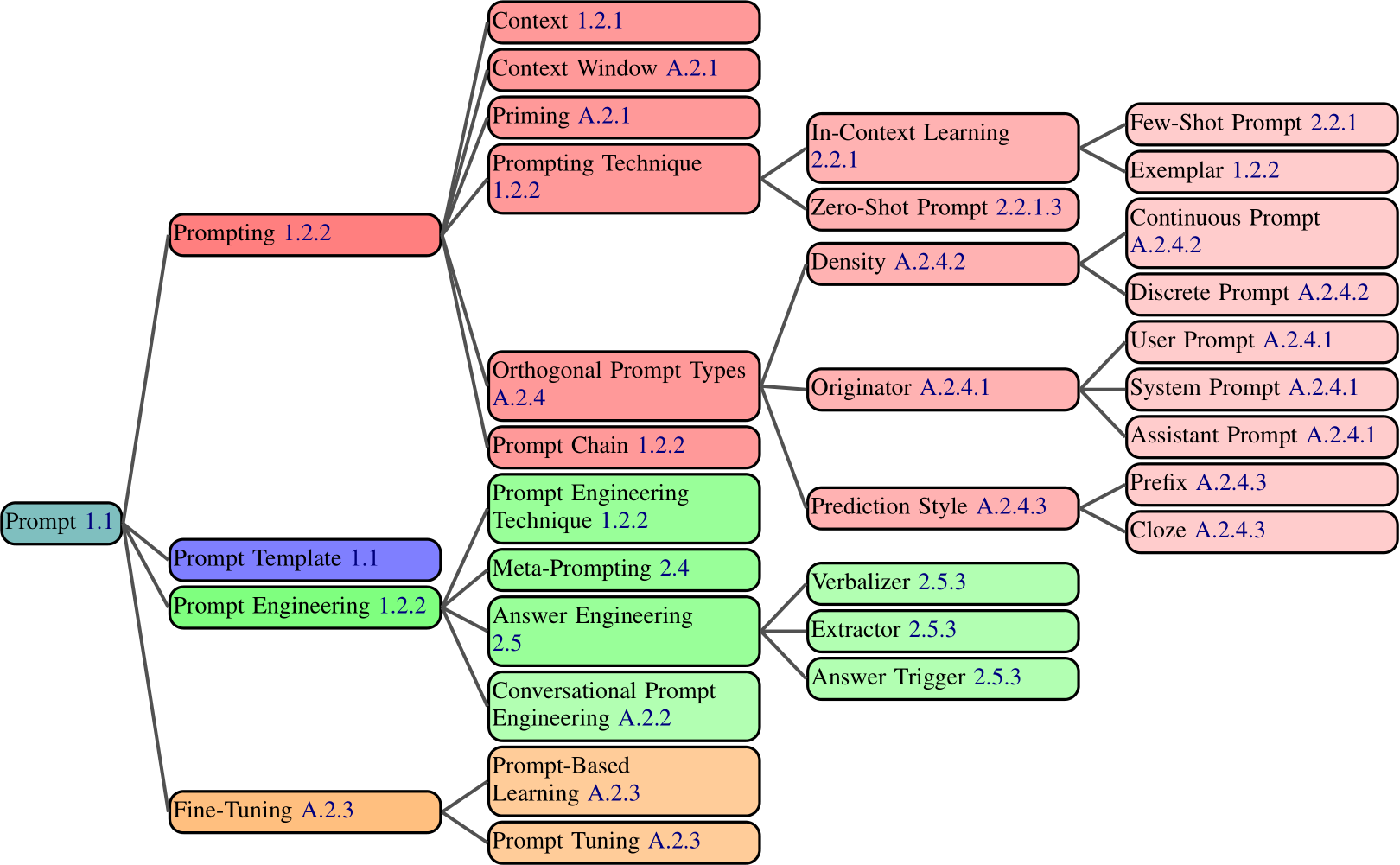

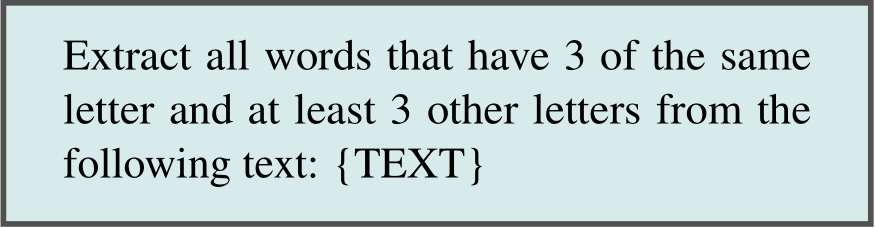

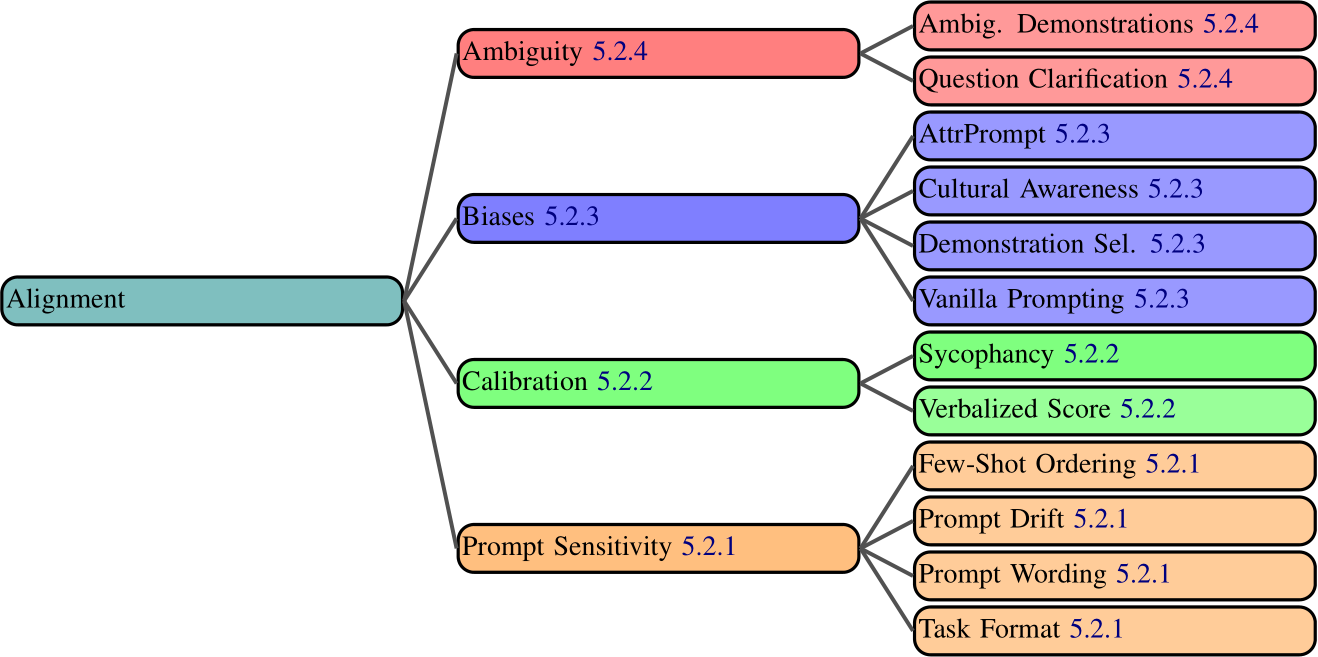

Figure 1.1: Categories within the field of prompting are interconnected. We discuss 7 core categories that are well described by the papers within our scope.

in the model’s vocabulary, while soft prompts may contain tokens that have no corresponding word in the vocabulary.

Finally, we only study task-agnostic techniques. These decisions keep the work approachable to less technical readers and maintain a manageable scope.

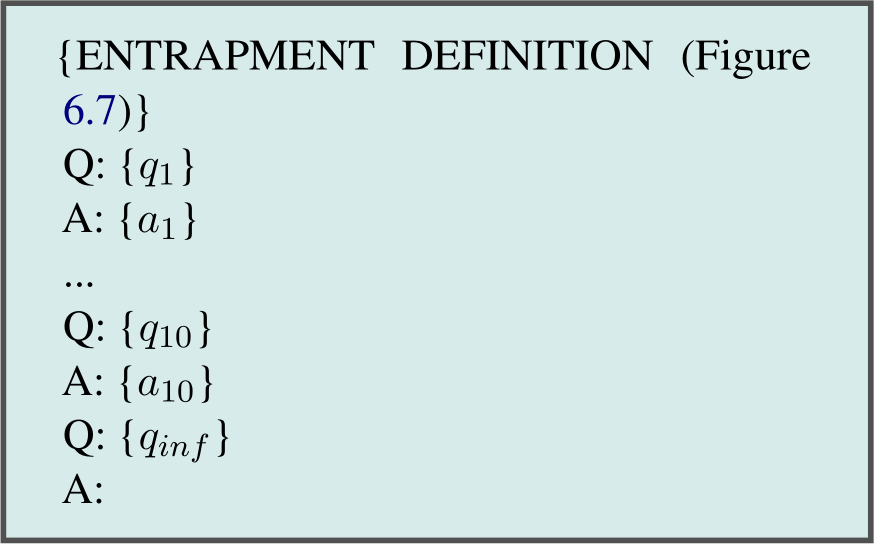

Sections Overview We conducted a machineassisted systematic review grounded in the PRISMA process (Page et al., 2021) (Section 2.1) to identify 58 different text-based prompting techniques, from which we create a taxonomy with a robust terminology of prompting terms (Section 1.2).

Our goal is to provide a roadmap for the community when considering which prompting techniques to use (Figure 1.1). While much literature on prompting focuses on English-only settings, we also discuss multilingual techniques (Section 3.1). Given the rapid growth in multimodal prompting, where prompts may include media such as images, we also expand our scope to multimodal techniques (Section 3.2). Many multilingual and multimodal prompting techniques are direct extensions of English text-only prompting techniques.

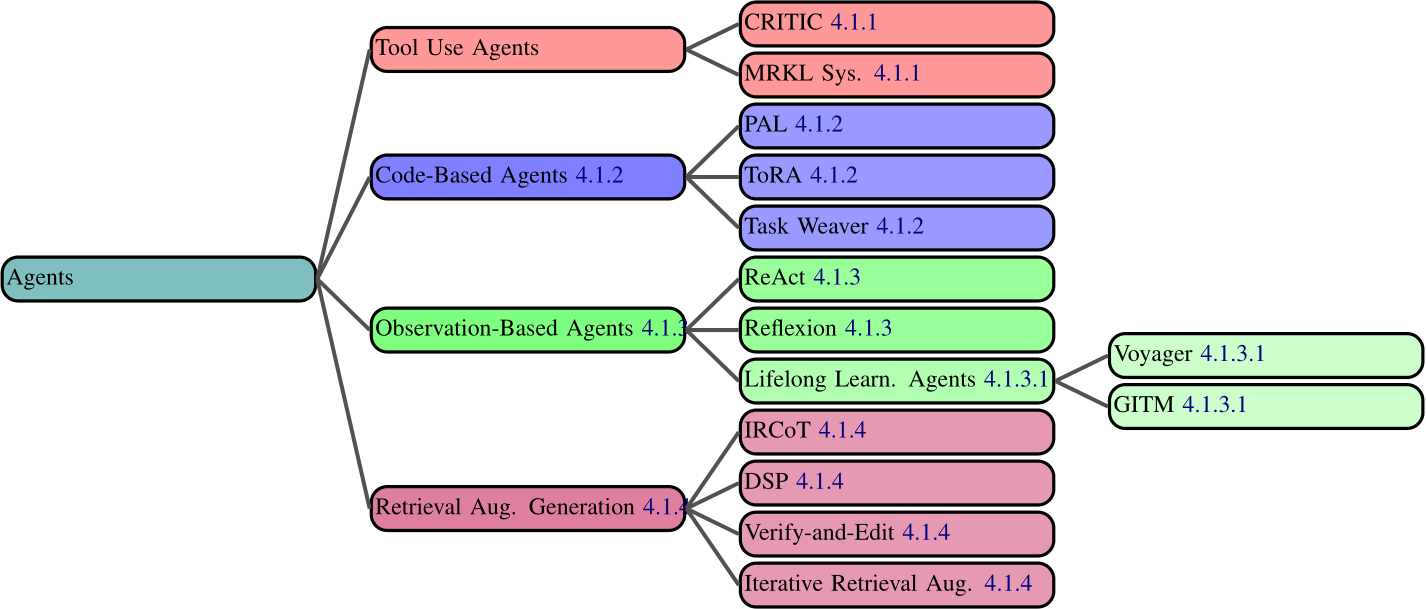

As prompting techniques grow more complex, they have begun to incorporate external tools, such as Internet browsing and calculators. We use the term "agents" to describe these types of prompting techniques (Section 4.1).

It is important to understand how to evaluate the outputs of agents and prompting techniques to ensure accuracy and avoid hallucinations. Thus, we discuss ways of evaluating these outputs (Section 4.2). We also discuss security (Section 5.1) and safety measures (Section 5.2) for designing prompts that reduce the risk of harm to companies and users.

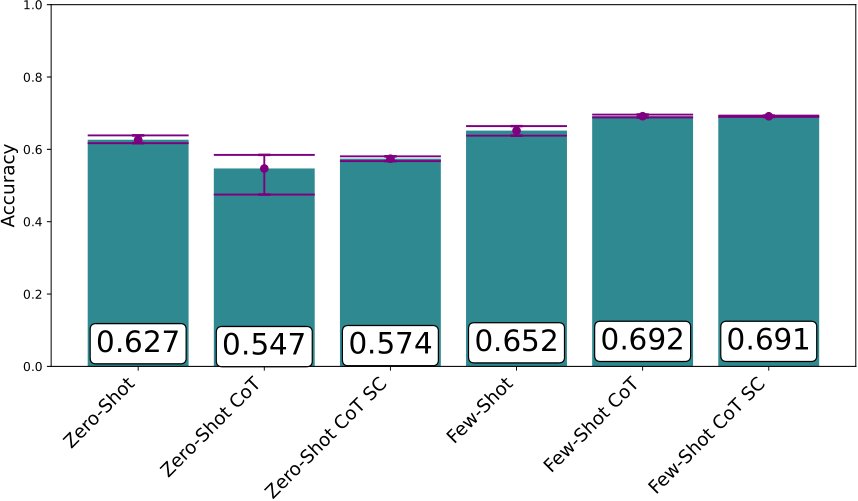

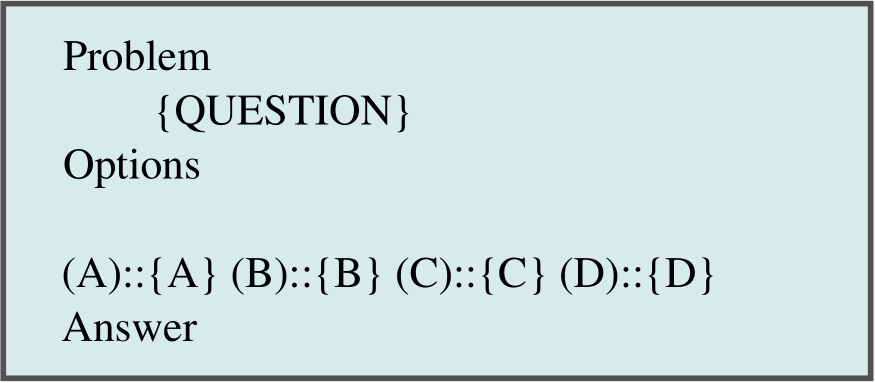

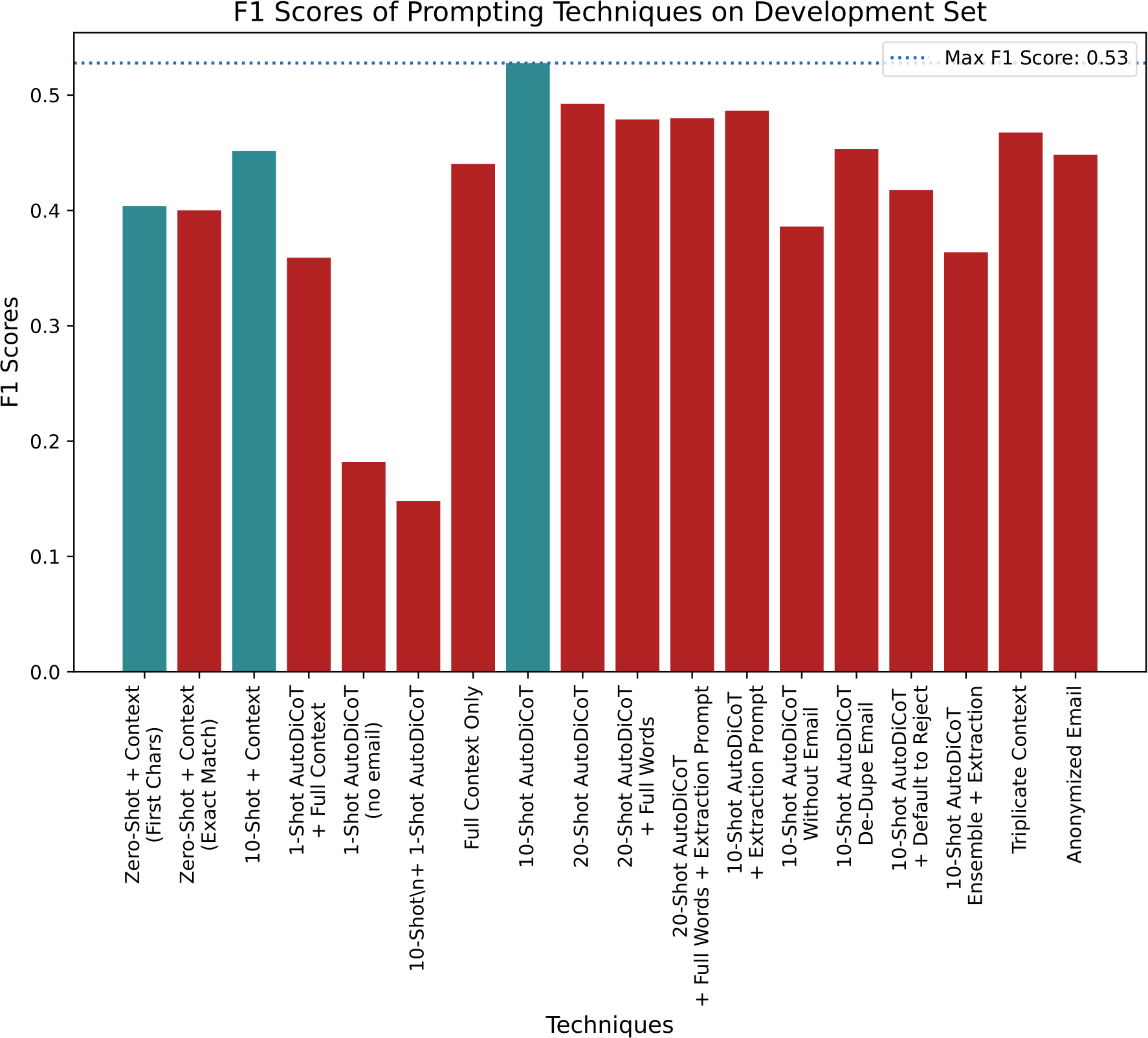

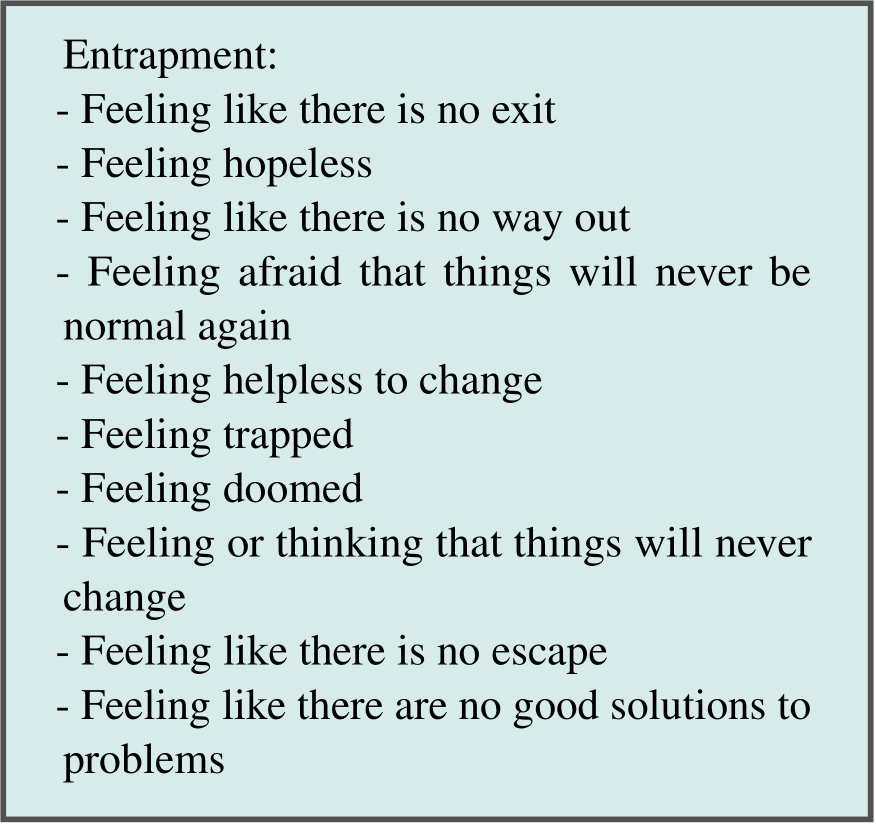

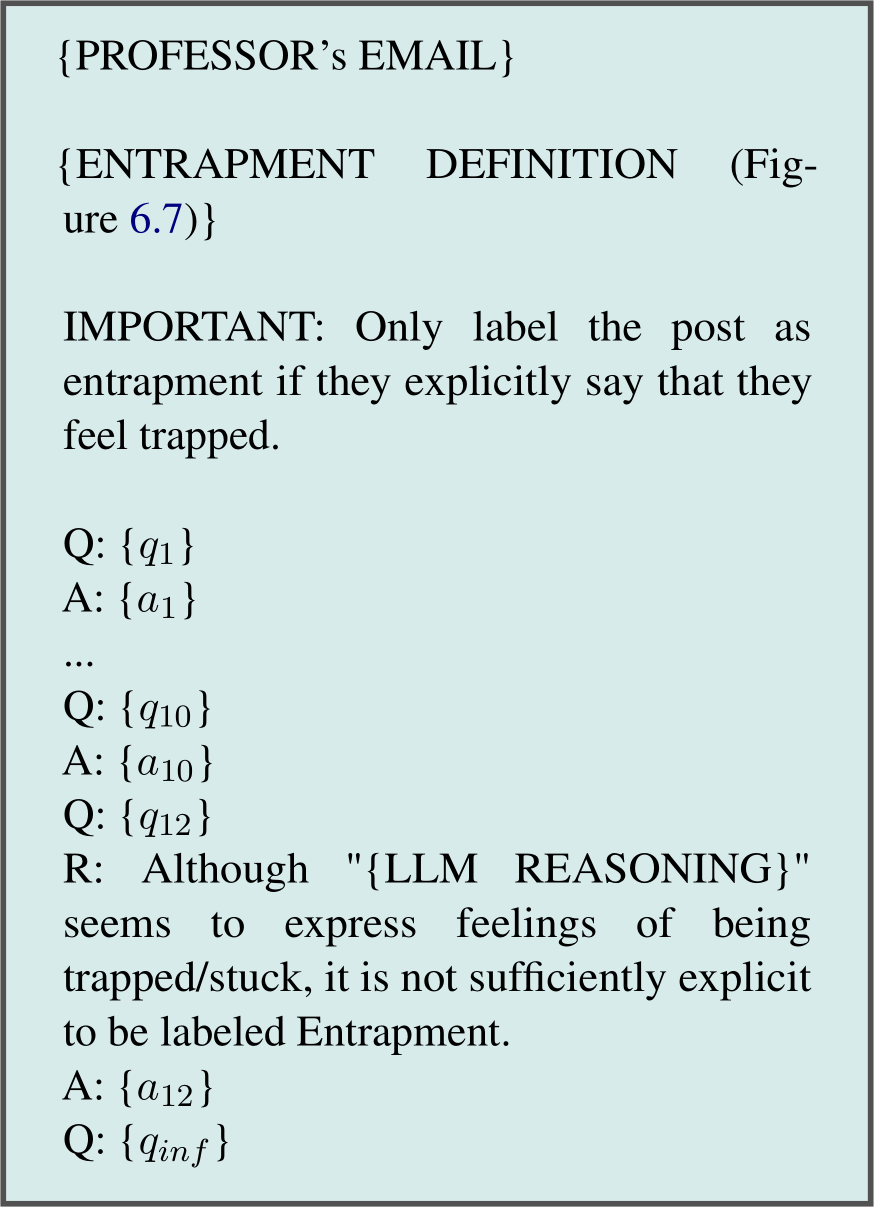

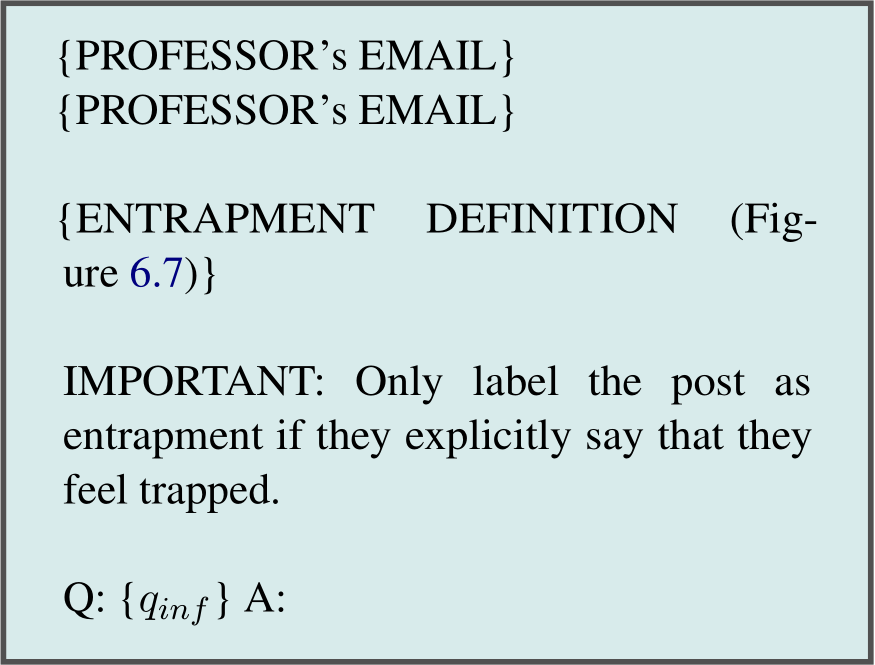

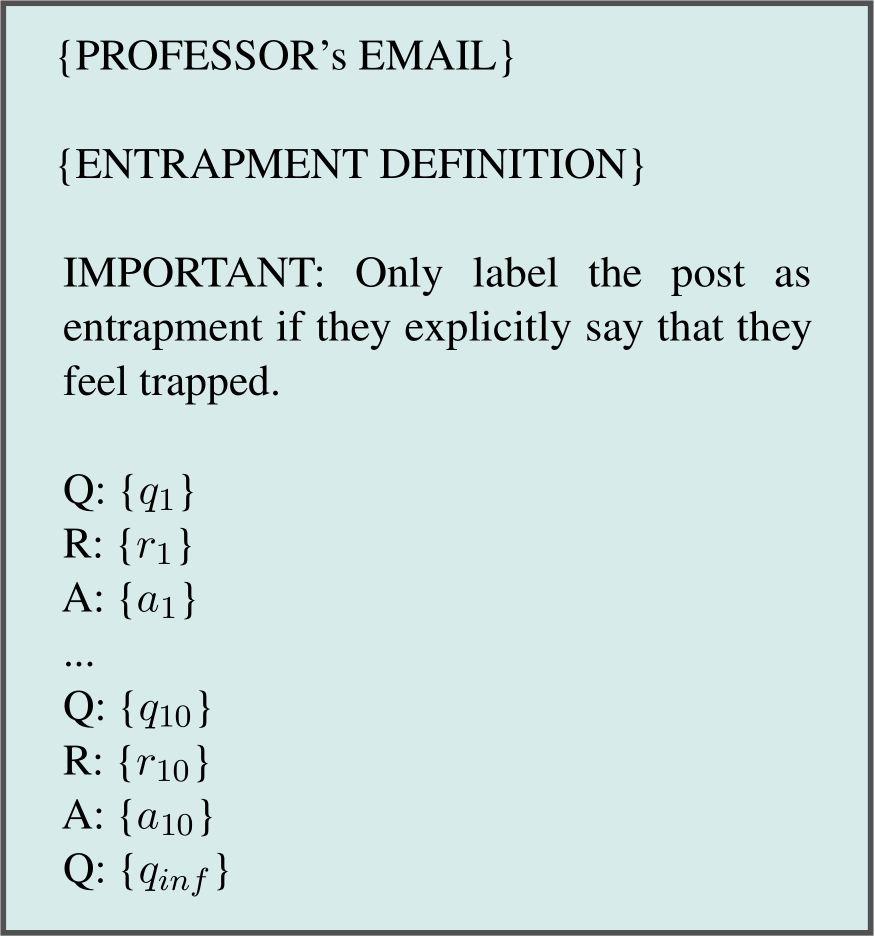

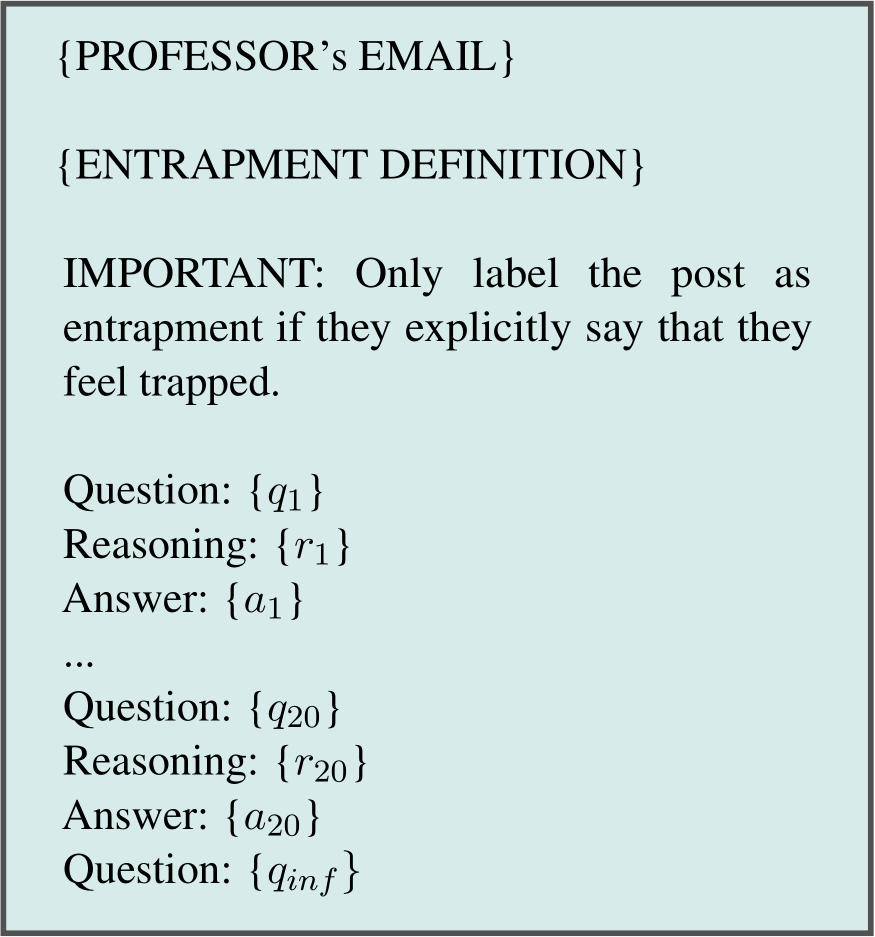

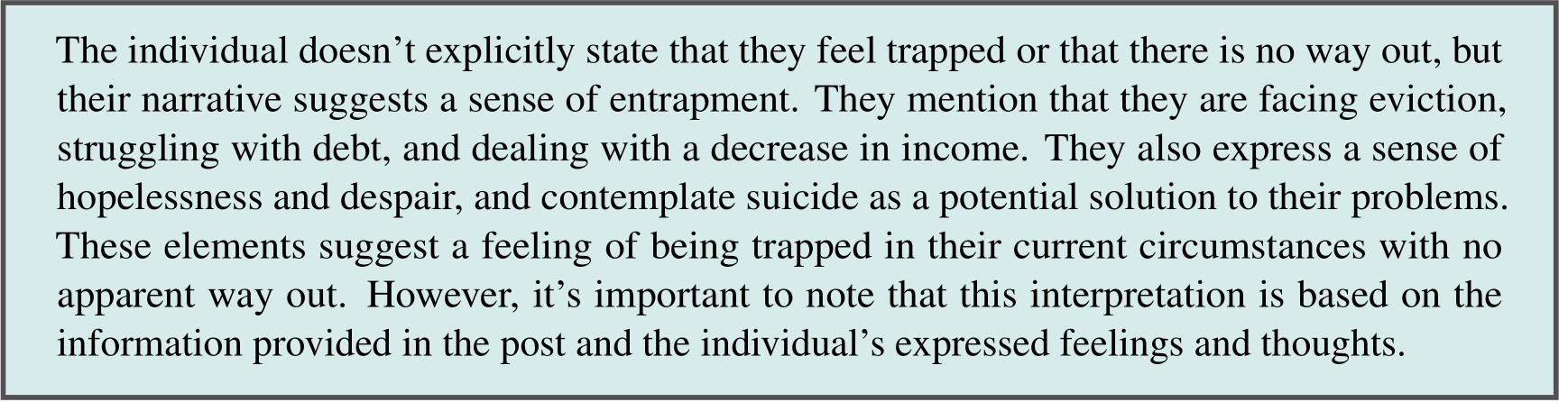

Finally, we apply prompting techniques in two case studies (Section 6.1). In the first, we test a range of prompting techniques against the commonly used benchmark MMLU (Hendrycks et al., 2021). In the second, we explore in detail an example of manual prompt engineering on a significant, real-world use case, identifying signals of frantic hopelessness–a top indicator of suicidal crisis–in the text of individuals seeking support (Schuck et al., 2019a). We conclude with a discussion of the nature of prompting and its recent development (Section 8).

1.1 What is a Prompt?

A prompt is an input to a Generative AI model, that is used to guide its output (Meskó, 2023; White et al., 2023; Heston and Khun, 2023; Hadi et al., 2023; Brown et al., 2020). Prompts may consist of text, image, sound, or other media. Some examples of prompts include the text, “write a three paragraph email for a marketing campaign for an accounting firm”, a photograph of a piece of paper with the words “what is 10*179” written on it, or a recording of an online meeting, with the instructions “summarize this”. Prompts usually have some text component, but this may change as non-text modalities become more common.

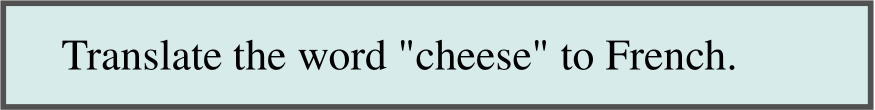

Prompt Template Prompts are often constructed via a prompt template (Shin et al., 2020b). A prompt template is a function that contains one or more variables which will be replaced by some media (usually text) to create a prompt. This prompt can then be considered to be an instance of the template.

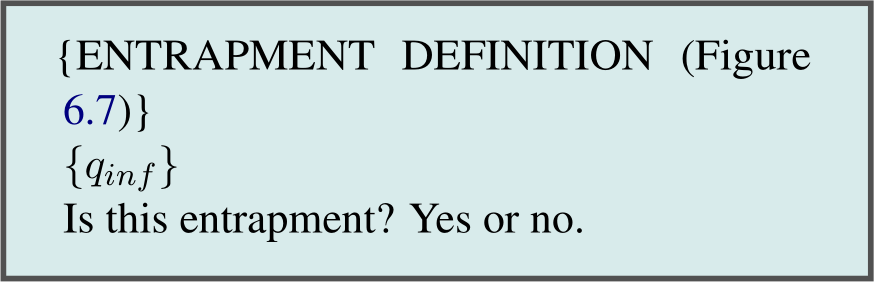

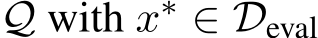

Consider applying prompting to the task of binary classification of tweets. Here is an initial prompt template that can be used to classify inputs.

![]()

Classify the tweet as positive or negative: {TWEET}

![]()

Figure 1.2: Prompts and prompt templates are distinct concepts; a prompt template becomes a prompt when input is inserted into it.

Each tweet in the dataset would be inserted into a separate instance of the template and the resulting prompt would be given to a LLM for inference.

1.2 Terminology

1.2.1 Components of a Prompt

There are a variety of common components included in a prompt. We summarize the most commonly used components and discuss how they fit into prompts (Figure 1.3).

Directive Many prompts issue a directive in the form of an instruction or question.1 This is the core intent of the prompt, sometimes simply called the "intent". For example, here is an instance of a prompt with a single instruction:

Directives can also be implicit, as in this one-shot case, where the directive is to perform English to Spanish translation:

Examples Examples, also known as exemplars or shots, act as demonstrations that guide the GenAI to accomplish a task. The above prompt is a OneShot (i.e. one example) prompt.

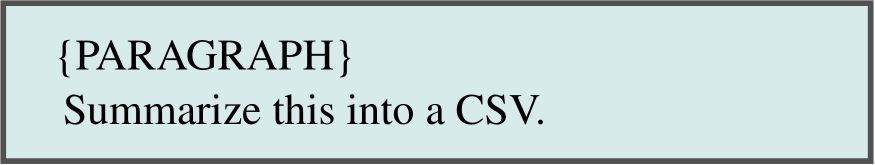

Output Formatting It is often desirable for the GenAI to output information in certain formats, for example, CSV, Markdown, XML, or even custom formats(Xia et al., 2024). Structuring outputs may reduce performance on some tasks (Tam et al., 2024). However, Kurt (2024) point out various

Figure 1.3: A Terminology of prompting. Terms with links to the appendix are not sufficiently critical to describe in the main paper, but are important to the field of prompting. Prompting techniques are shown in Figure 2.2

![]()

flaws in Tam et al. (2024) and show that structuring outputs may actually improve performance. Here is an example of how you might format a prompt to output information as a CSV:

Style Instructions Style instructions are a type of output formatting used to modify the output stylistically rather than structurally (Section 2.2.1.3). For example:

![]()

Write a clear and curt paragraph about llamas.

![]()

Role A Role, also known as a persona (Schmidt et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023l), is a frequently discussed component that can improve writing and style text (Section 2.2.1.3). For example:

Additional Information It is often necessary to include additional information in the prompt. For example, if the directive is to write an email, you might include information such as your name and position so the GenAI can properly sign the email. Additional Information is sometimes called ‘context‘, though we discourage the use of this term as it is overloaded with other meanings in the prompting space2.

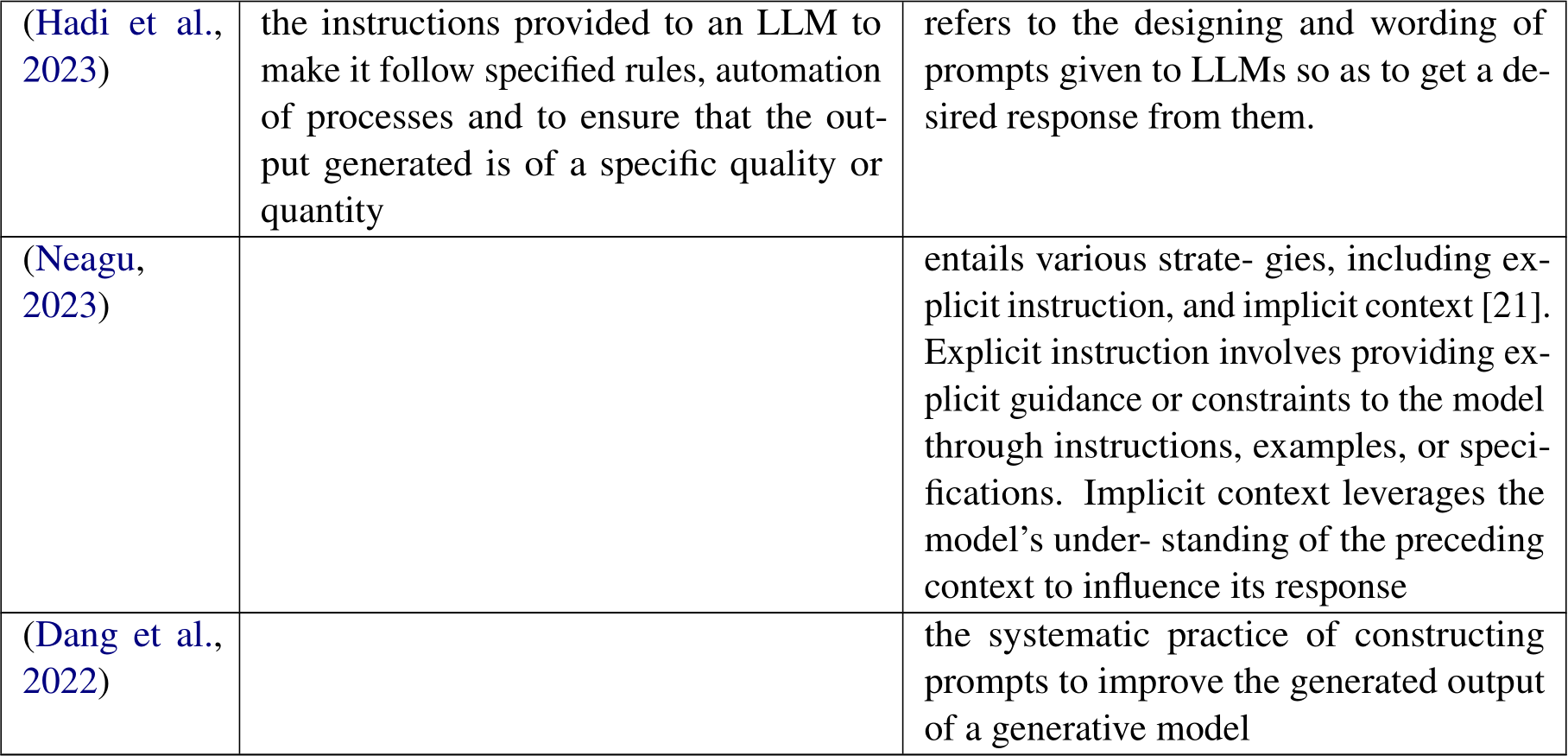

1.2.2 Prompting Terms

Terminology within the prompting literature is rapidly developing. As it stands, there are many poorly understood definitions (e.g. prompt, prompt engineering) and conflicting ones (e.g. role prompt vs persona prompt). The lack of a consistent vocabulary hampers the community’s ability to clearly describe the various prompting techniques in use. We provide a robust vocabulary of terms used in the prompting community (Figure 1.3).3 Less frequent terms are left to Appendix A.2. In order to accurately define frequently-used terms like prompt and prompt engineering, we integrate many definitions (Appendix A.1) to derive representative definitions.

Prompting Prompting is the process of providing a prompt to a GenAI, which then generates a response. For example, the action of sending a

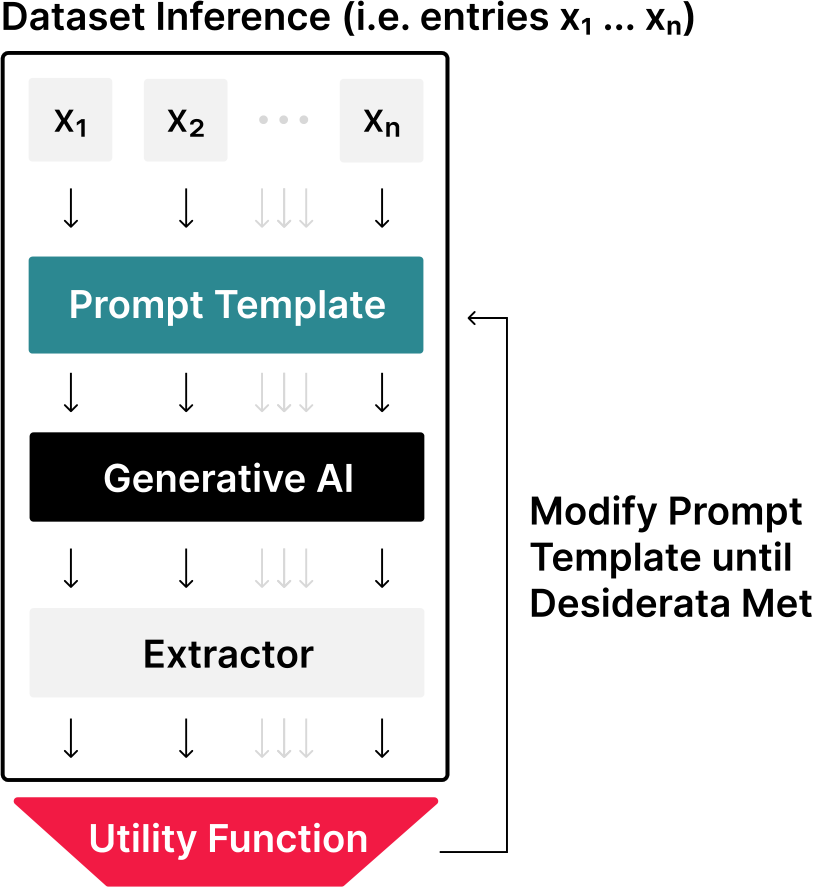

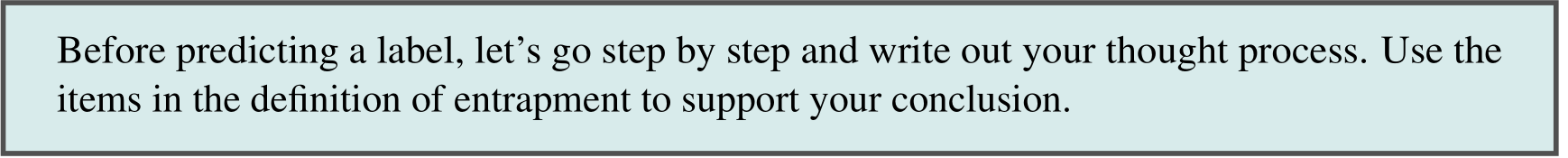

Figure 1.4: The Prompt Engineering Process consists of three repeated steps 1) performing inference on a dataset 2) evaluating performance and 3) modifying the prompt template. Note that the extractor is used to extract a final response from the LLM output (e.g. "This phrase is positive" ![]() "positive"). See more information on extractors in Section 2.5.

"positive"). See more information on extractors in Section 2.5.

chunk of text or uploading an image constitutes prompting.

Prompt Chain A prompt chain (activity: prompt chaining) consists of two or more prompt templates used in succession. The output of the prompt generated by the first prompt template is used to parameterize the second template, continuing until all templates are exhausted (Wu et al., 2022).

Prompting Technique A prompting technique is a blueprint that describes how to structure a prompt, prompts, or dynamic sequencing of multiple prompts. A prompting technique may incorporate conditional or branching logic, parallelism, or other architectural considerations spanning multiple prompts.

Prompt Engineering Prompt engineering is the iterative process of developing a prompt by modifying or changing the prompting technique that you are using (Figure 1.4).

Prompt Engineering Technique A prompt engineering technique is a strategy for iterating on a prompt to improve it. In literature, this will often be automated techniques (Deng et al., 2022), but in consumer settings, users often perform prompt engineering manually, without any assistive tooling. Exemplar Exemplars are examples of a task being completed that are shown to a model in a prompt (Brown et al., 2020).

1.3 A Short History of Prompts

The idea of using natural language prefixes, or prompts, to elicit language model behaviors and responses originated before the GPT-3 and ChatGPT era. GPT-2 (Radford et al., 2019a) makes use of prompts and they appear to be first used in the context of Generative AI by Fan et al. (2018). However, the concept of prompts was preceded by related concepts such as control codes (Pfaff, 1979; Poplack, 1980; Keskar et al., 2019) and writing prompts in literature.

The term Prompt Engineering appears to have come into existence more recently from Radford et al. (2021) then slightly later from Reynolds and McDonell (2021).

However, various papers perform prompt engineering without naming the term (Wallace et al., 2019; Shin et al., 2020a), including Schick and Schütze (2020a,b); Gao et al. (2021) for nonautoregressive language models.

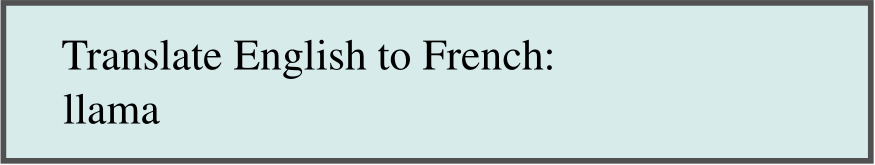

Some of the first works on prompting define a prompt slightly differently to how it is currently used. For example, consider the following prompt from Brown et al. (2020):

Brown et al. (2020) consider the word "llama" to be the prompt, while "Translate English to French:" is the "task description". More recent papers, including this one, refer to the entire string passed to the LLM as the prompt.

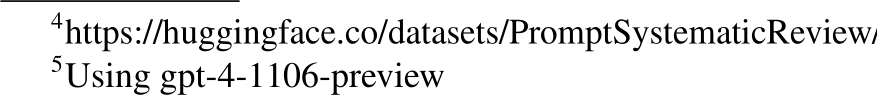

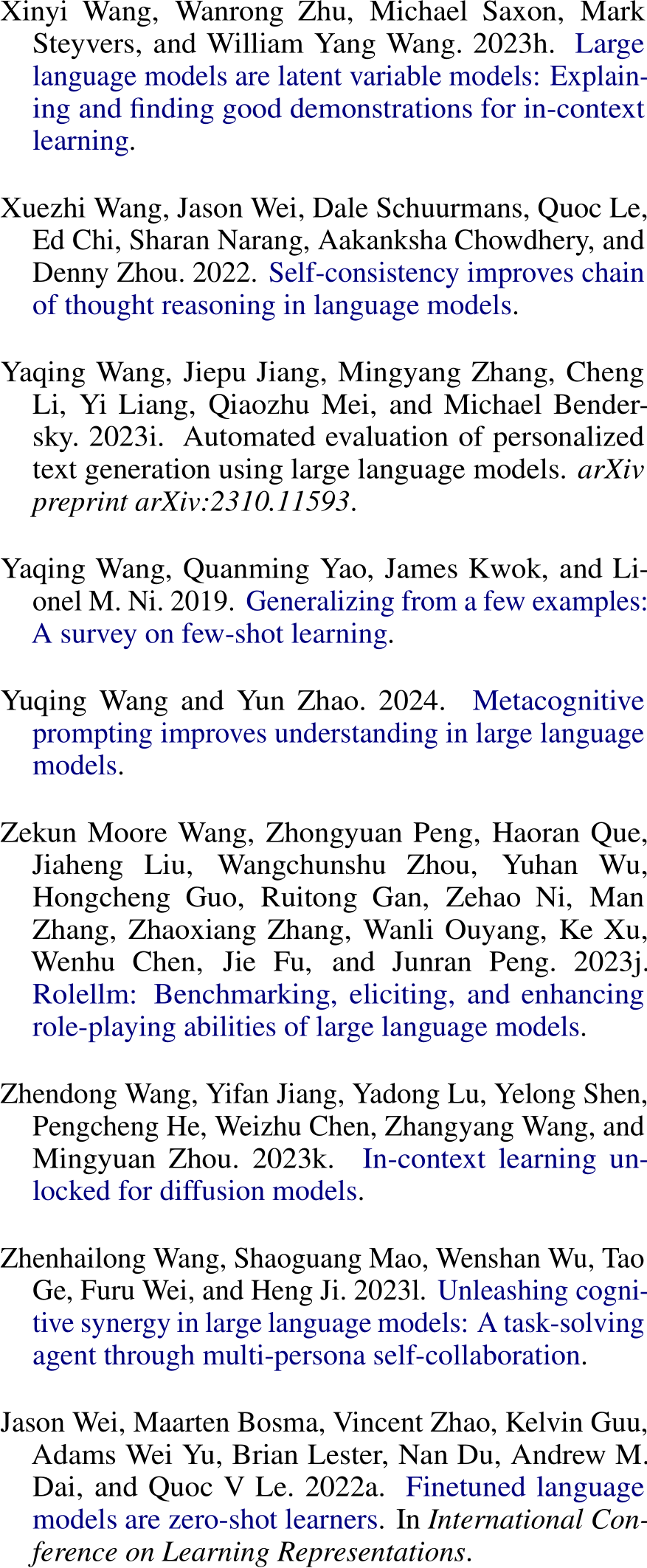

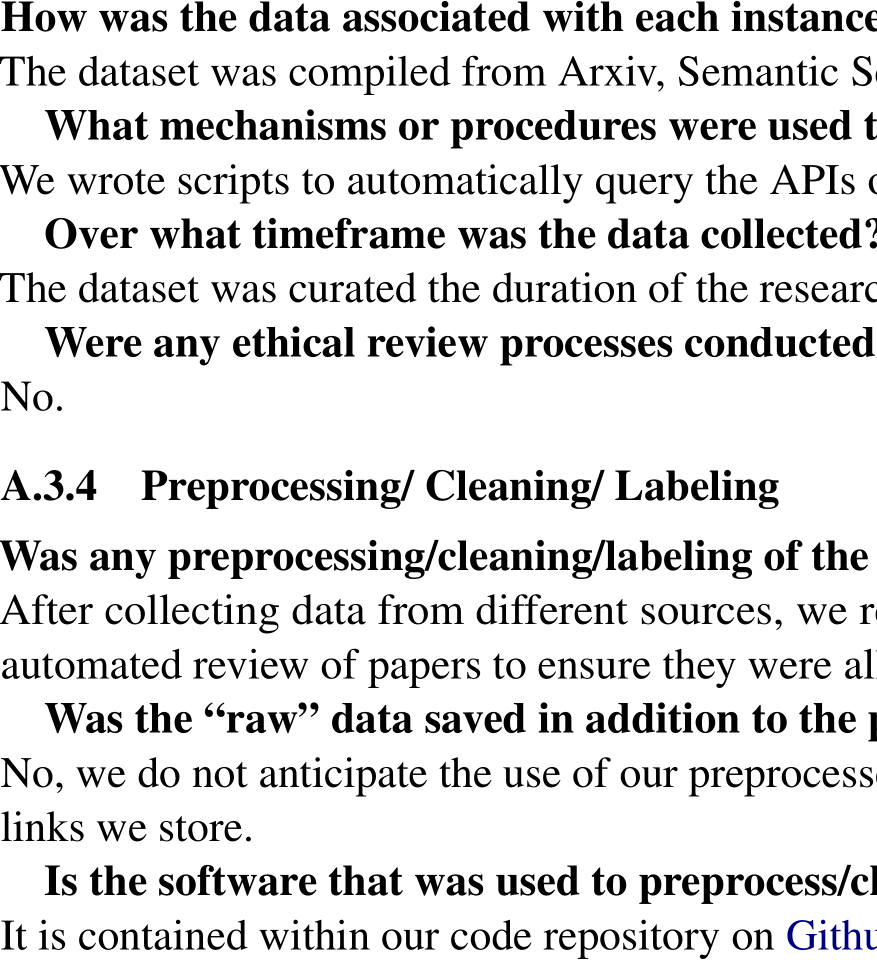

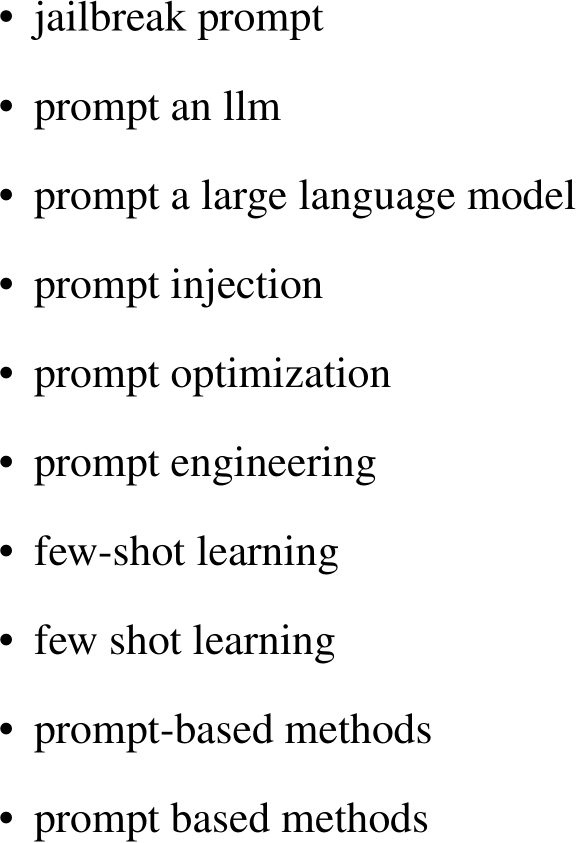

2.1 Systematic Review Process

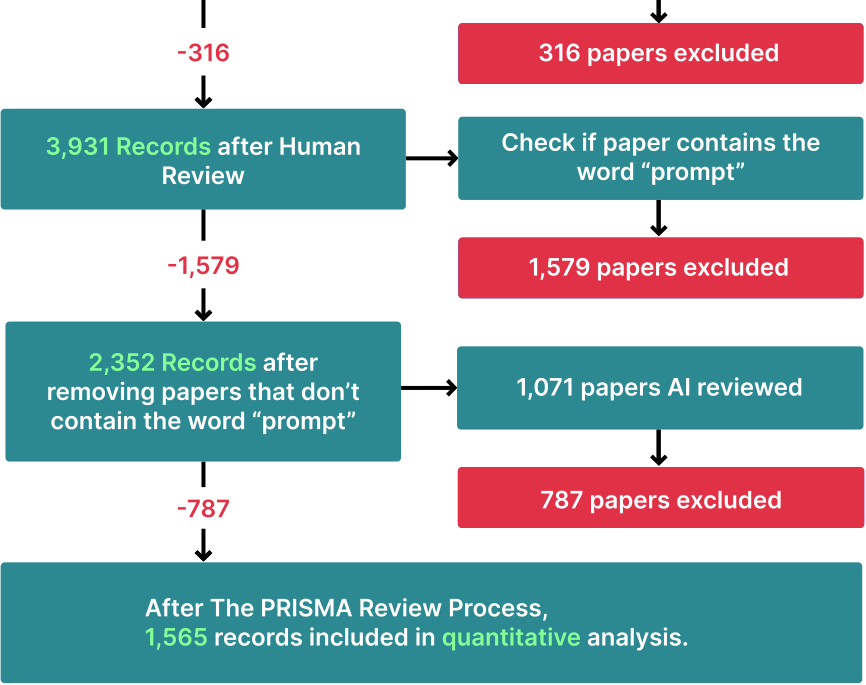

In order to robustly collect a dataset of sources for this paper, we ran a systematic literature review grounded in the PRISMA process (Page et al., 2021) (Figure 2.1). We host this dataset on HuggingFace 4 and present a datasheet (Gebru et al., 2021) for the dataset in Appendix A.3. Our main data sources were arXiv, Semantic Scholar, and ACL. We query these databases with a list of 44 keywords narrowly related to prompting and prompt engineering (Appendix A.4).

2.1.1 The Pipeline

In this section, we introduce our data scraping pipeline, which includes both human and LLMassisted review.5 As an initial sample to establish filtering critera, we retrieve papers from arXiv based on a simple set of keywords and boolean rules (A.4). Then, human annotators label a sample of 1,661 articles from the arXiv set for the following criteria:

1. Include if the paper proposes a novel prompting technique.

2. Include if the paper strictly covers hard prefix prompts.

3. Exclude if the paper focuses on training by backpropagating gradients.

4. Include if the paper uses a masked frame and/or window for non-text modalities.

A set of 300 articles are reviewed independently by two annotators, with 92% agreement (Krippendorff’s ![]() a prompt using gpt-4-1106-preview to classify the remaining articles (Appendix A.5). We validate the prompt against 100 ground-truth annotations, achieving 89% precision and 75% recall (for an F1 of 81%). The combined human and LLM annotations generate a final set of 1,565 papers.

a prompt using gpt-4-1106-preview to classify the remaining articles (Appendix A.5). We validate the prompt against 100 ground-truth annotations, achieving 89% precision and 75% recall (for an F1 of 81%). The combined human and LLM annotations generate a final set of 1,565 papers.

4,247 Records after Title Deduplication 1,661 papers human reviewed

Figure 2.1: The PRISMA systematic literature review process. We accumulate 4,247 unique records from which we extract 1,565 relevant records.

2.2 Text-Based Techniques

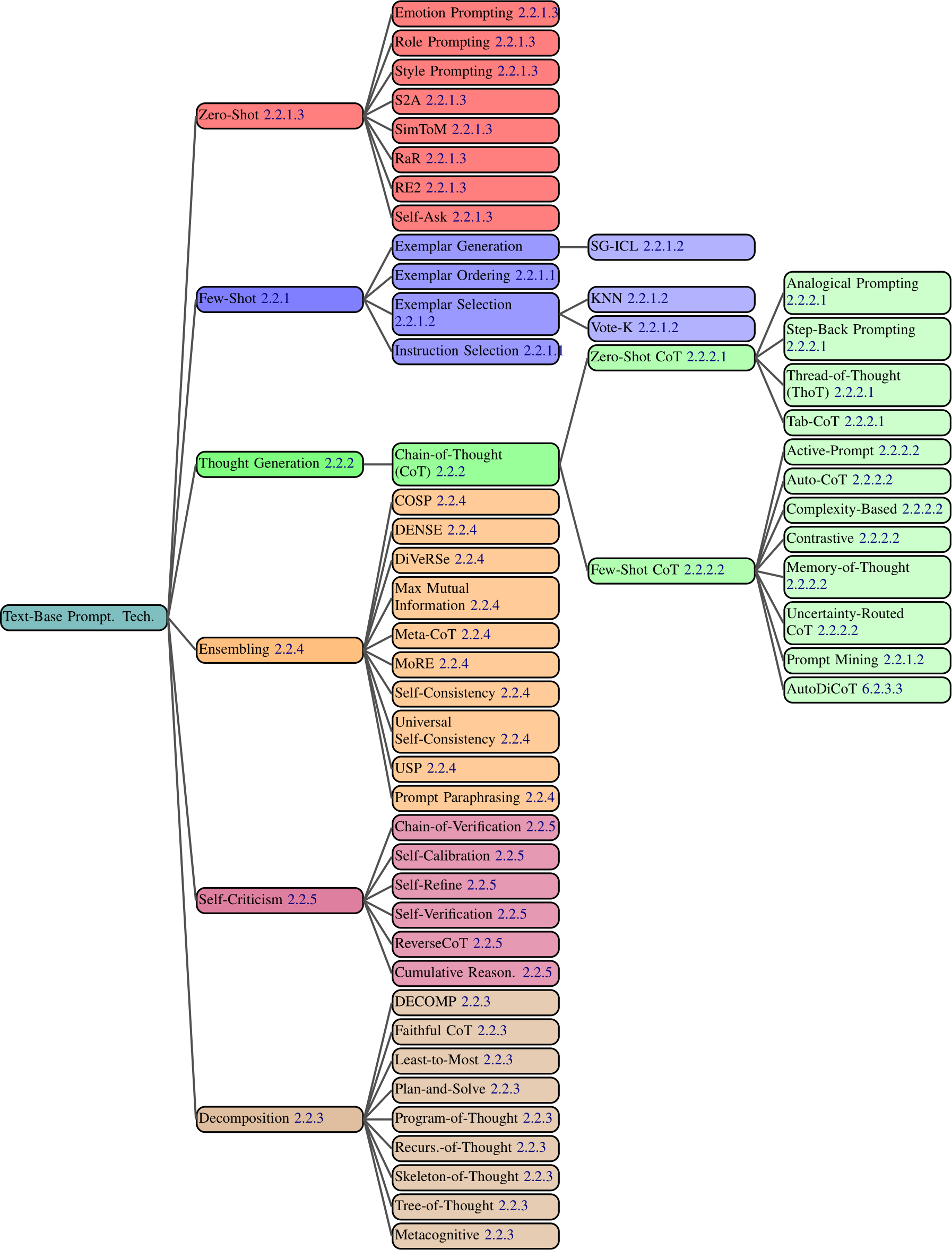

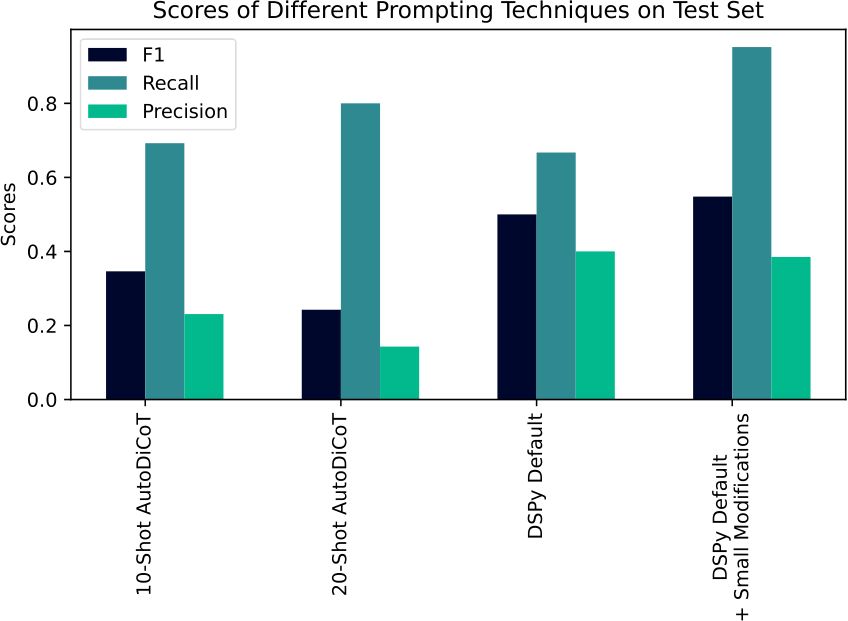

We now present a comprehensive taxonomical ontology of 58 text-based prompting techniques, broken into 6 major categories (Figure 2.2). Although some of the techniques might fit into multiple categories, we place them in a single category of most relevance.

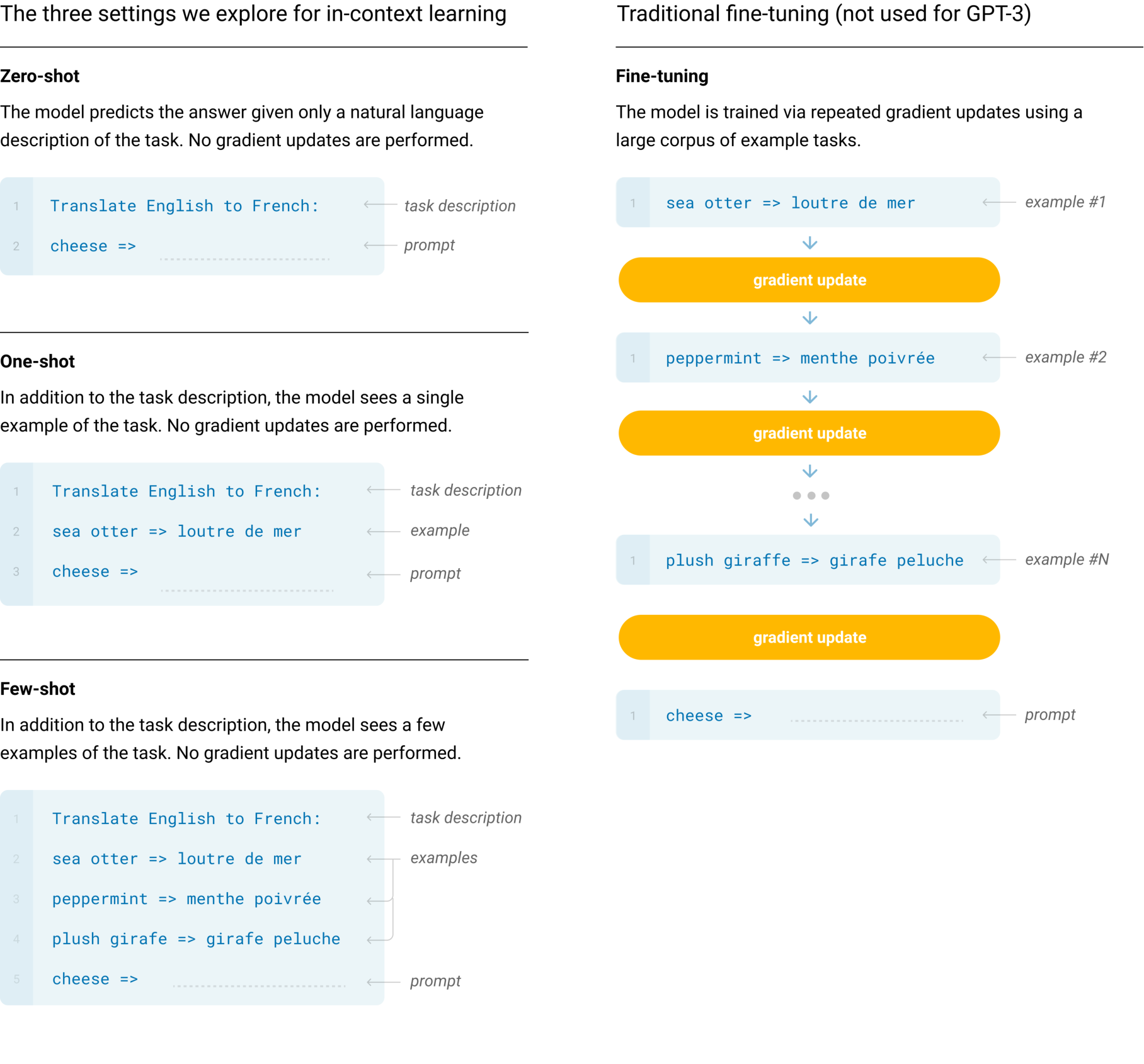

2.2.1 In-Context Learning (ICL)

ICL refers to the ability of GenAIs to learn skills and tasks by providing them with exemplars and or relevant instructions within the prompt, without the need for weight updates/retraining (Brown et al., 2020; Radford et al., 2019b). These skills can be learned from exemplars (Figure 2.4) and/or instructions (Figure 2.5). Note that the word "learn" is misleading. ICL can simply be task specification– the skills are not necessarily new, and can have already been included in the training data (Figure 2.6). See Appendix A.9 for a discussion of the use of this term. Significant work is currently being done on optimizing (Bansal et al., 2023) and understanding (Si et al., 2023a; Štefánik and Kadlˇcík, 2023) ICL.

Figure 2.2: All text-based prompting techniques from our dataset.

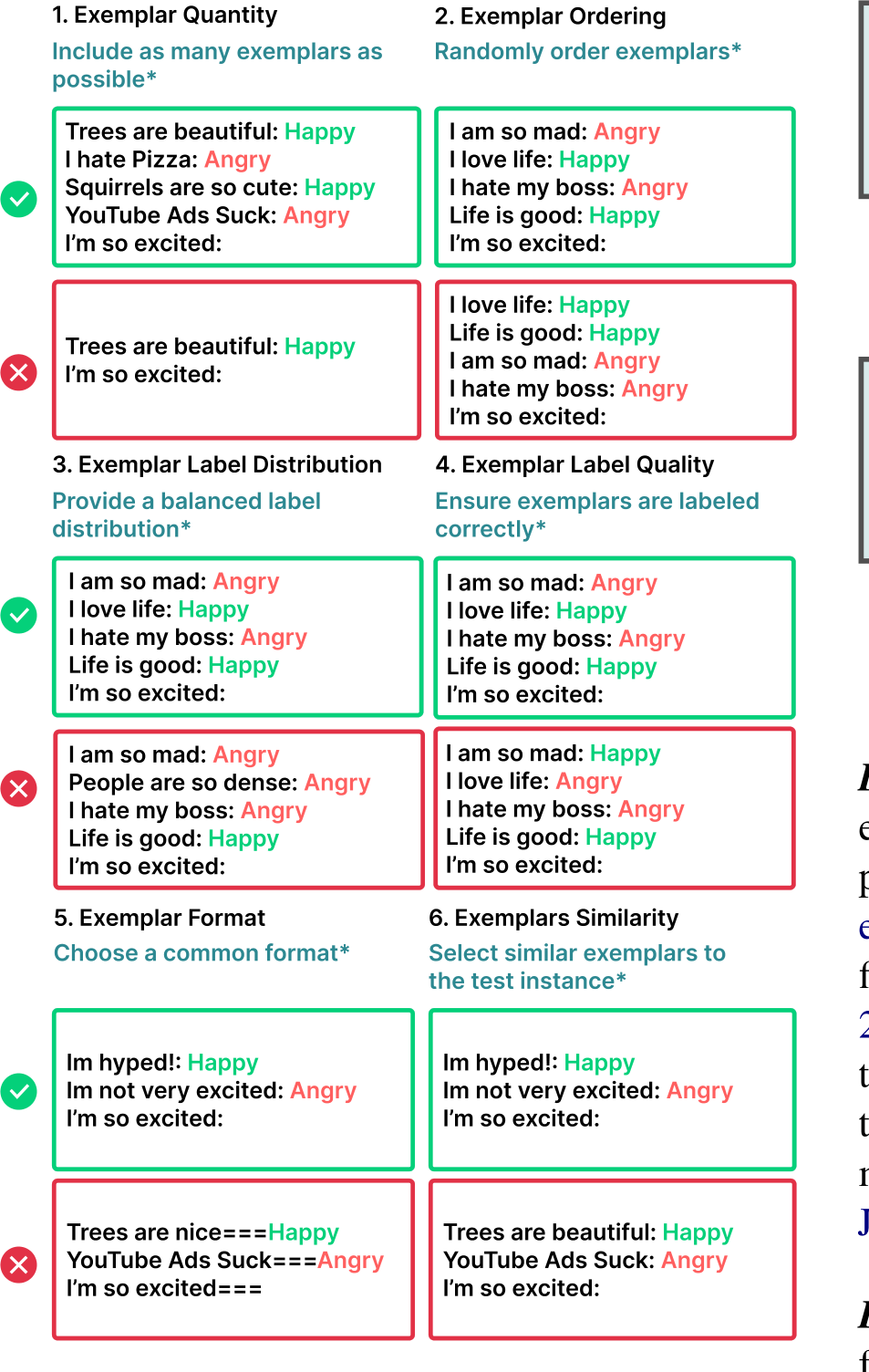

Figure 2.3: We highlight six main design decisions when crafting few-shot prompts. ![]() Please note that recommendations here do not generalize to all tasks; in some cases, each of them could hurt performance.

Please note that recommendations here do not generalize to all tasks; in some cases, each of them could hurt performance.

Few-Shot Prompting (Brown et al., 2020) is the paradigm seen in Figure 2.4, where the GenAI learns to complete a task with only a few examples (exemplars). Few-shot prompting is a special case of Few-Shot Learning (FSL) (Fei-Fei et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2019), but does not require updating of model parameters

2.2.1.1 Few-Shot Prompting Design Decisions

Selecting exemplars for a prompt is a difficult task– performance depends significantly on various factors of the exemplars (Dong et al., 2023), and only a limited number of exemplars fit in the typical LLM’s context window. We highlight six separate design decisions, including the selection and order of exemplars that critically influence the output quality (Zhao et al., 2021a; Lu et al., 2021; Ye and Durrett, 2023) (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.4: ICL exemplar prompt

Figure 2.5: ICL instruction prompt

Exemplar Quantity Increasing the quantity of exemplars in the prompt generally improves model performance, particularly in larger models (Brown et al., 2020). However, in some cases, the benefits may diminish beyond 20 exemplars (Liu et al., 2021). In the case of long context LLMs, additional exemplars continue to increase performance, though efficiency varies depending on task and model (Agarwal et al., 2024; Bertsch et al., 2024; Jiang et al., 2024).

Exemplar Ordering The order of exemplars affects model behavior (Lu et al., 2021; Kumar and Talukdar, 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Rubin et al., 2022). On some tasks, exemplar order can cause accuracy to vary from sub-50% to 90%+ (Lu et al., 2021).

Exemplar Label Distribution As in traditional supervised machine learning, the distribution of exemplar labels in the prompt affects behavior. For example, if 10 exemplars from one class and 2 exemplars of another class are included, this may cause the model to be biased toward the first class.

Exemplar Label Quality Despite the general benefit of multiple exemplars, the necessity of strictly valid demonstrations is unclear. Some work (Min et al., 2022) suggests that the accuracy of labels is irrelevant—providing models with exemplars with incorrect labels may not negatively diminish performance. However, under certain settings, there is a significant impact on performance (Yoo et al., 2022). Larger models are often better at handling incorrect or unrelated labels (Wei et al., 2023c).

It is important to discuss this factor, since if you are automatically constructing prompts from large datasets that may contain inaccuracies, it may be

Figure 2.6: ICL from training data prompt. In this version of ICL, the model is not learning a new skill, but rather using knowledge likely in its training set.

necessary to study how label quality affects your results.

Exemplar Format The formatting of exemplars also affects performance. One of the most common formats is “Q: {input}, A: {label}”, but the optimal format may vary across tasks; it may be worth trying multiple formats to see which performs best. There is some evidence to suggest that formats that occur commonly in the training data will lead to better performance (Jiang et al., 2020).

Exemplar Similarity Selecting exemplars that are similar to the test sample is generally beneficial for performance (Liu et al., 2021; Min et al., 2022). However, in some cases, selecting more diverse exemplars can improve performance (Su et al., 2022; Min et al., 2022).

Instruction Selection While instructions are required to guide LLMs in zero-shot prompts (Wei et al., 2022a), the benefits of adding instructions before exemplars in few-shot prompts is less clear. Ajith et al. (2024) show that generic, task-agnostic instructions (i.e., no instruction or “Complete the following task:”) improve classification and question answering accuracy over task-specific ones (e.g., What is the answer to this question?) concluding instruction-following abilities can be achieved via exemplars alone. While they may not improve correctness, instructions in few-shot prompts can still guide auxiliary output attributes like writing style (Roy et al., 2023).

2.2.1.2 Few-Shot Prompting Techniques Considering all of these factors, Few-Shot Prompting can be very difficult to implement effectively. We now examine techniques for Few-Shot Prompting in the supervised setting. Ensembling approaches can also benefit Few-Shot Prompting, but we discuss them separately (Section 2.2.4).

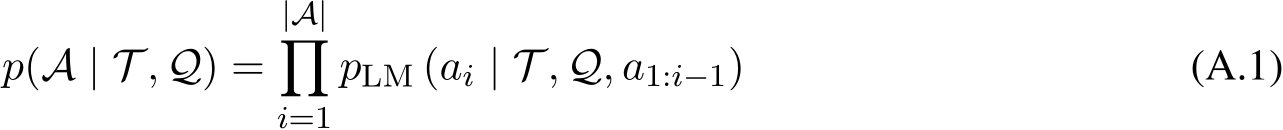

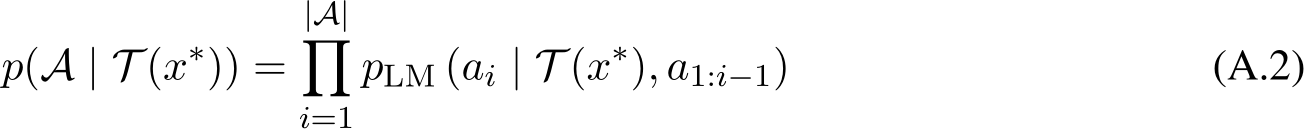

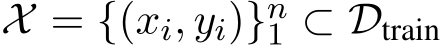

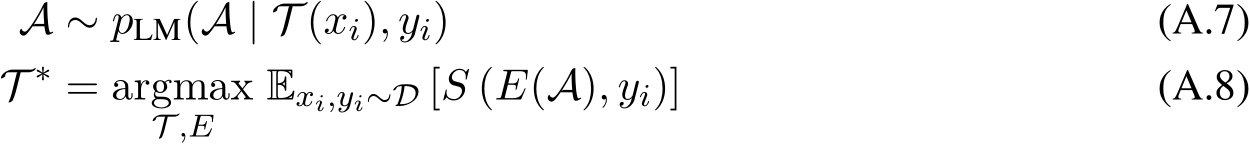

Assume we have a training dataset,  , which contains multiple inputs

, which contains multiple inputs  and outputs

and outputs  , which can be used to few-shot prompt a GenAI (rather than performing gradient-based updates). Assume that this prompt can be dynamically generated with respect to

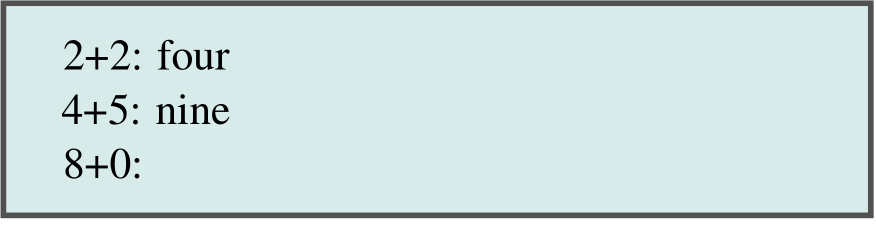

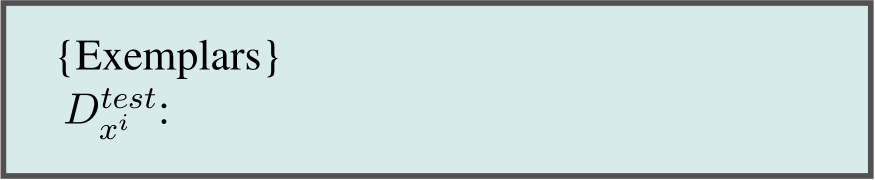

, which can be used to few-shot prompt a GenAI (rather than performing gradient-based updates). Assume that this prompt can be dynamically generated with respect to  at test time. Here is the prompt template we will use for this section, following the ‘input: output‘ format (Figure 2.4):

at test time. Here is the prompt template we will use for this section, following the ‘input: output‘ format (Figure 2.4):

Figure 2.7: Few-Shot Prompting Template

K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) (Liu et al., 2021) is part of a family of algorithms that selects exemplars similar to  to boost performance. Although effective, employing KNN during prompt generation may be time and resource intensive.

to boost performance. Although effective, employing KNN during prompt generation may be time and resource intensive.

Vote-K (Su et al., 2022) is another method to select similar exemplars to the test sample. In one stage, a model proposes useful unlabeled candidate exemplars for an annotator to label. In the second stage, the labeled pool is used for Few-Shot Prompting. Vote-K also ensures that newly added exemplars are sufficiently different than existing ones to increase diversity and representativeness.

Self-Generated In-Context Learning (SG-ICL) (Kim et al., 2022) leverages a GenAI to automatically generate exemplars. While better than zero-shot scenarios when training data is unavailable, the generated samples are not as effective as actual data.

Prompt Mining (Jiang et al., 2020) is the process of discovering optimal "middle words" in prompts through large corpus analysis. These middle words are effectively prompt templates. For example, instead of using the common "Q: A:" format for few-shot prompts, there may exist something similar that occurs more frequently in the corpus. Formats which occur more often in the corpus will likely lead to improved prompt performance.

More Complicated Techniques such as LENS (Li and Qiu, 2023a), UDR (Li et al., 2023f), and Active Example Selection (Zhang et al., 2022a) leverage iterative filtering, embedding and retrieval, and reinforcement learning, respectively.

2.2.1.3 Zero-Shot Prompting Techniques

In contrast to Few-Shot Prompting, Zero-Shot Prompting uses zero exemplars. There are a number of well-known standalone zero-shot techniques as well as zero-shot techniques combined with another concept (e.g. Chain of Thought), which we discuss later (Section 2.2.2).

Role Prompting (Wang et al., 2023j; Zheng et al., 2023d) , also known as persona prompting (Schmidt et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023l), assigns a specific role to the GenAI in the prompt. For example, the user might prompt it to act like "Madonna" or a "travel writer". This can create more desirable outputs for open-ended tasks (Reynolds and McDonell, 2021) and in some cases may improve accuracy on benchmarks (Zheng et al., 2023d).

Style Prompting (Lu et al., 2023a) involves specifying the desired style, tone, or genre in the prompt to shape the output of a GenAI. A similar effect can be achieved using role prompting.

Emotion Prompting (Li et al., 2023a) incorporates phrases of psychological relevance to humans (e.g., "This is important to my career") into the prompt, which may lead to improved LLM performance on benchmarks and open-ended text generation.

System 2 Attention (S2A) (Weston and Sukhbaatar, 2023) first asks an LLM to rewrite the prompt and remove any information unrelated to the question therein. Then, it passes this new prompt into an LLM to retrieve a final response.

SimToM (Wilf et al., 2023) deals with complicated questions which involve multiple people or objects. Given the question, it attempts to establish the set of facts one person knows, then answer the question based only on those facts. This is a two prompt process and can help eliminate the effect of irrelevant information in the prompt.

Rephrase and Respond (RaR) (Deng et al., 2023) instructs the LLM to rephrase and expand the question before generating the final answer. For example, it might add the following phrase to the question: "Rephrase and expand the question, and respond". This could all be done in a single pass or the new question could be passed to the LLM separately. RaR has demonstrated improvements on multiple benchmarks.

Re-reading (RE2) (Xu et al., 2023) adds the phrase "Read the question again:" to the prompt in addition to repeating the question. Although this is such a simple technique, it has shown improvement

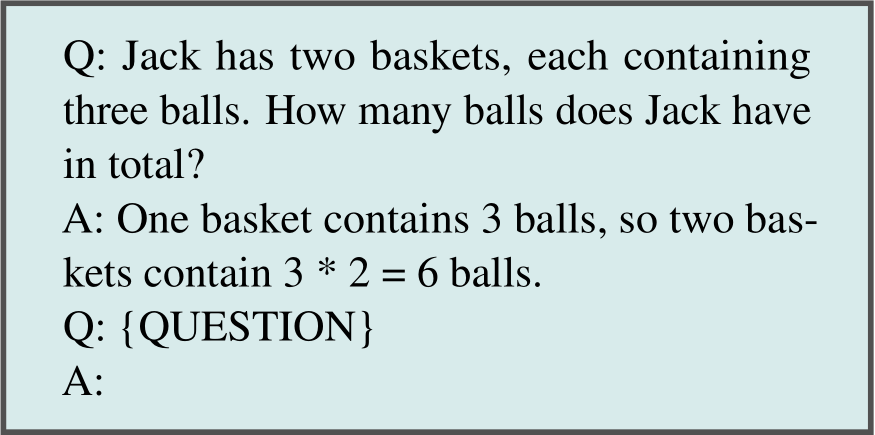

Figure 2.8: A One-Shot Chain-of-Thought Prompt.

in reasoning benchmarks, especially with complex questions.

Self-Ask (Press et al., 2022) prompts LLMs to first decide if they need to ask follow up questions for a given prompt. If so, the LLM generates these questions, then answers them and finally answers the original question.

2.2.2 Thought Generation

Thought generation encompasses a range of techniques that prompt the LLM to articulate its reasoning while solving a problem (Zhang et al., 2023c).

Chain-of-Thought (CoT) Prompting (Wei et al.,

2022b) leverages few-shot prompting to encourage the LLM to express its thought process before delivering its final answer.6 This technique is occasionally referred to as Chain-of-Thoughts (Tutunov et al., 2023; Besta et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2023d). It has been demonstrated to significantly enhance the LLM’s performance in mathematics and reasoning tasks. In Wei et al. (2022b), the prompt includes an exemplar featuring a question, a reasoning path, and the correct answer (Figure 2.8).

2.2.2.1 Zero-Shot-CoT

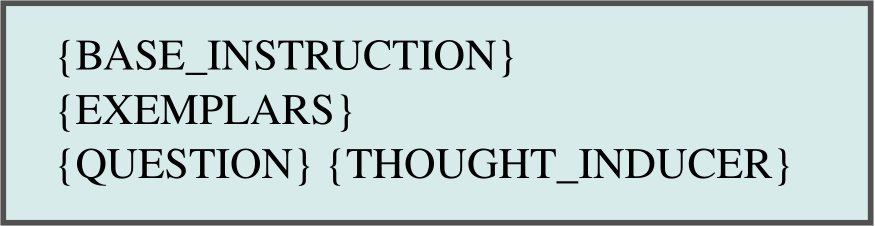

The most straightforward version of CoT contains zero exemplars. It involves appending a thought inducing phrase like "Let’s think step by step." (Kojima et al., 2022) to the prompt. Other suggested thought-generating phrases include "First, let’s think about this logically" (Kojima et al., 2022). Zhou et al. (2022b) uses LLMs to generate "Let’s work this out in a step by step way to be sure we have the right answer". Yang et al. (2023a) searches for an optimal thought inducer. Zero-Shot-CoT approaches are attractive as they don’t require exemplars and are generally task agnostic.

Step-Back Prompting (Zheng et al., 2023c) is a modification of CoT where the LLM is first asked a generic, high-level question about relevant concepts or facts before delving into reasoning. This approach has improved performance significantly on multiple reasoning benchmarks for both PaLM-2L and GPT-4.

Analogical Prompting (Yasunaga et al., 2023) is similar to SG-ICL, and automatically generates exemplars that include CoTs. It has demonstrated improvements in mathematical reasoning and code generation tasks.

Thread-of-Thought (ThoT) Prompting (Zhou et al., 2023) consists of an improved thought inducer for CoT reasoning. Instead of "Let’s think step by step," it uses "Walk me through this context in manageable parts step by step, summarizing and analyzing as we go." This thought inducer works well in question-answering and retrieval settings, especially when dealing with large, complex contexts.

Tabular Chain-of-Thought (Tab-CoT) (Jin and Lu, 2023) consists of a Zero-Shot CoT prompt that makes the LLM output reasoning as a markdown table. This tabular design enables the LLM to improve the structure and thus the reasoning of its output.

2.2.2.2 Few-Shot CoT

This set of techniques presents the LLM with multiple exemplars, which include chains-of-thought. This can significantly enhance performance. This technique is occasionally referred to as ManualCoT (Zhang et al., 2022b) or Golden CoT (Del and Fishel, 2023).

Contrastive CoT Prompting (Chia et al., 2023) adds both exemplars with incorrect and correct explanations to the CoT prompt in order to show the LLM how not to reason. This method has shown significant improvement in areas like Arithmetic Reasoning and Factual QA.

Uncertainty-Routed CoT Prompting (Google, 2023) samples multiple CoT reasoning paths, then selects the majority if it is above a certain threshold (calculated based on validation data). If not, it samples greedily and selects that response. This method demonstrates improvement on the MMLU benchmark for both GPT-4 and Gemini Ultra models.

Complexity-based Prompting (Fu et al., 2023b) involves two major modifications to CoT. First, it selects complex examples for annotation and inclusion in the prompt, based on factors like question length or reasoning steps required. Second, during inference, it samples multiple reasoning chains (answers) and uses a majority vote among chains exceeding a certain length threshold, under the premise that longer reasoning indicates higher answer quality. This technique has shown improvements on three mathematical reasoning datasets.

Active Prompting (Diao et al., 2023) starts with some training questions/exemplars, asks the LLM to solve them, then calculates uncertainty (disagreement in this case) and asks human annotators to rewrite the exemplars with highest uncertainty.

Memory-of-Thought Prompting (Li and Qiu, 2023b) leverage unlabeled training exemplars to build Few-Shot CoT prompts at test time. Before test time, it performs inference on the unlabeled training exemplars with CoT. At test time, it retrieves similar instances to the test sample. This technique has shown substantial improvements in benchmarks like Arithmetic, commonsense, and factual reasoning.

Automatic Chain-of-Thought (Auto-CoT) Prompt- ing (Zhang et al., 2022b) uses Wei et al. (2022b)’s Zero-Shot prompt to automatically generate chains of thought. These are then used to build a Few-Shot CoT prompt for a test sample.

2.2.3 Decomposition

Significant research has focused on decomposing complex problems into simpler sub-questions. This is an effective problem-solving strategy for humans as well as GenAI (Patel et al., 2022). Some decomposition techniques are similar to thought-inducing techniques, such as CoT, which often naturally breaks down problems into simpler components. However, explicitly breaking down problems can further improve LLMs’ problem solving ability.

Least-to-Most Prompting (Zhou et al., 2022a) starts by prompting a LLM to break a given problem into sub-problems without solving them. Then, it solves them sequentially, appending model responses to the prompt each time, until it arrives

at a final result. This method has shown significant improvements in tasks involving symbolic manipulation, compositional generalization, and mathematical reasoning.

Decomposed Prompting (DECOMP) (Khot et al., 2022) Few-Shot prompts a LLM to show it how to use certain functions. These might include things like string splitting or internet searching; these are often implemented as separate LLM calls. Given this, the LLM breaks down its original problem into sub-problems which it sends to different functions. It has shown improved performance over Least-to-Most prompting on some tasks.

Plan-and-Solve Prompting (Wang et al., 2023f) consists of an improved Zero-Shot CoT prompt, "Let’s first understand the problem and devise a plan to solve it. Then, let’s carry out the plan and solve the problem step by step". This method generates more robust reasoning processes than standard Zero-Shot-CoT on multiple reasoning datasets.

Tree-of-Thought (ToT) (Yao et al., 2023b), also known as Tree of Thoughts, (Long, 2023), creates a tree-like search problem by starting with an initial problem then generating multiple possible steps in the form of thoughts (as from a CoT). It evaluates the progress each step makes towards solving the problem (through prompting) and decides which steps to continue with, then keeps creating more thoughts. ToT is particularly effective for tasks that require search and planning.

Recursion-of-Thought (Lee and Kim, 2023) is similar to regular CoT. However, every time it encounters a complicated problem in the middle of its reasoning chain, it sends this problem into another prompt/LLM call. After this is completed, the answer is inserted into the original prompt. In this way, it can recursively solve complex problems, including ones which might otherwise run over that maximum context length. This method has shown improvements on arithmetic and algorithmic tasks. Though implemented using fine-tuning to output a special token that sends sub-problem into another prompt, it could also be done only through prompting.

Program-of-Thoughts (Chen et al., 2023d) uses LLMs like Codex to generate programming code as reasoning steps. A code interpreter executes these steps to obtain the final answer. It excels in mathematical and programming-related tasks but is less effective for semantic reasoning tasks.

Faithful Chain-of-Thought (Lyu et al., 2023) generates a CoT that has both natural language and symbolic language (e.g. Python) reasoning, just like Program-of-Thoughts. However, it also makes use of different types of symbolic languages in a task-dependent fashion.

Skeleton-of-Thought (Ning et al., 2023) focuses on accelerating answer speed through parallelization. Given a problem, it prompts an LLM to create a skeleton of the answer, in a sense, sub-problems to be solved. Then, in parallel, it sends these questions to a LLM and concatenates all the outputs to get a final response.

Metacognitive Prompting (Wang and Zhao, 2024) attempts to make the LLM mirror human metacognitive processes with a five part prompt chain, with steps including clarifying the question, preliminary judgement, evaluation of response, decision confirmation, and confidence assessment.

2.2.4 Ensembling

In GenAI, ensembling is the process of using multiple prompts to solve the same problem, then aggregating these responses into a final output. In many cases, a majority vote—selecting the most frequent response—is used to generate the final output. Ensembling techniques reduce the variance of LLM outputs and often improving accuracy, but come with the cost of increasing the number of model calls needed to reach a final answer.

Demonstration Ensembling (DENSE) (Khalifa et al., 2023) creates multiple few-shot prompts, each containing a distinct subset of exemplars from the training set. Next, it aggregates over their outputs to generate a final response.

Mixture of Reasoning Experts (MoRE) (Si et al., 2023d) creates a set of diverse reasoning experts by using different specialized prompts for different reasoning types (such as retrieval augmentation prompts for factual reasoning, Chain-of-Thought reasoning for multi-hop and math reasoning, and generated knowledge prompting for commonsense reasoning). The best answer from all experts is selected based on an agreement score.

Max Mutual Information Method (Sorensen et al., 2022) creates multiple prompt templates with varied styles and exemplars, then selects the optimal template as the one that maximizes mutual information between the prompt and the LLM’s outputs.

Self-Consistency (Wang et al., 2022) is based on the intuition that multiple different reasoning paths can lead to the same answer. This method first prompts the LLM multiple times to perform CoT, crucially with a non-zero temperature to elicit diverse reasoning paths. Next, it uses a majority vote over all generated responses to select a final response. Self-Consistency has shown improvements on arithmetic, commonsense, and symbolic reasoning tasks.

Universal Self-Consistency (Chen et al., 2023e) is similar to Self-Consistency except that rather than selecting the majority response by programmatically counting how often it occurs, it inserts all outputs into a prompt template that selects the majority answer. This is helpful for free-form text generation and cases where the same answer may be output slightly differently by different prompts.

Meta-Reasoning over Multiple CoTs (Yoran et al., 2023) is similar to universal SelfConsistency; it first generates multiple reasoning chains (but not necessarily final answers) for a given problem. Next, it inserts all of these chains in a single prompt template then generates a final answer from them.

DiVeRSe (Li et al., 2023i) creates multiple prompts for a given problem then performs SelfConsistency for each, generating multiple reasoning paths. They score reasoning paths based on each step in them then select a final response.

Consistency-based Self-adaptive Prompting (COSP) (Wan et al., 2023a) constructs Few-Shot CoT prompts by running Zero-Shot CoT with Self-Consistency on a set of examples then selecting a high agreement subset of the outputs to be included in the final prompt as exemplars. It again performs Self-Consistency with this final prompt.

Universal Self-Adaptive Prompting (USP) (Wan et al., 2023b) builds upon the success of COSP, aiming to make it generalizable to all tasks. USP makes use of unlabeled data to generate exemplars and a more complicated scoring function to select them. Additionally, USP does not use Self-Consistency.

Prompt Paraphrasing (Jiang et al., 2020) transforms an original prompt by changing some of the wording, while still maintaining the overall meaning. It is effectively a data augmentation technique that can be used to generate prompts for an ensemble.

2.2.5 Self-Criticism

When creating GenAI systems, it can be useful to have LLMs criticize their own outputs (Huang et al., 2022). This could simply be a judgement (e.g., is this output correct) or the LLM could be prompted to provide feedback, which is then used to improve the answer. Many approaches to generating and integrating self-criticism have been developed.

Self-Calibration (Kadavath et al., 2022) first prompts an LLM to answer a question. Then, it builds a new prompt that includes the question, the LLM’s answer, and an additional instruction asking whether the answer is correct. This can be useful for gauging confidence levels when applying LLMs when deciding when to accept or revise the original answer.

Self-Refine (Madaan et al., 2023) is an iterative framework where, given an initial answer from the LLM, it prompts the same LLM to provide feedback on the answer, and then prompts the LLM to improve the answer based on the feedback. This iterative process continues until a stopping condition is met (e.g., max number of steps reached). Self-Refine has demonstrated improvement across a range of reasoning, coding, and generation tasks.

Reversing Chain-of-Thought (RCoT) (Xue et al., 2023) first prompts LLMs to reconstruct the problem based on generated answer. Then, it generates fine-grained comparisons between the original problem and the reconstructed problem as a way to check for any inconsistencies. These inconsistencies are then converted to feedback for the LLM to revise the generated answer.

Self-Verification (Weng et al., 2022) generates multiple candidate solutions with Chain-of-Thought (CoT). It then scores each solution by masking certain parts of the original question and asking an LLM to predict them based on the rest of the question and the generated solution. This method has shown improvement on eight reasoning datasets.

Chain-of-Verification (COVE) (Dhuliawala et al., 2023) first uses an LLM to generate an answer to a given question. Then, it creates a list of related questions that would help verify the correctness of the answer. Each question is answered by the LLM, then all the information is given to the LLM to produce the final revised answer. This method has shown improvements in various question-answering and text-generation tasks.

Cumulative Reasoning (Zhang et al., 2023b)

first generates several potential steps in answering the question. It then has a LLM evaluate them, deciding to either accept or reject these steps. Finally, it checks whether it has arrived at the final answer. If so, it terminates the process, but otherwise it repeats it. This method has demonstrated improvements in logical inference tasks and mathematical problem.

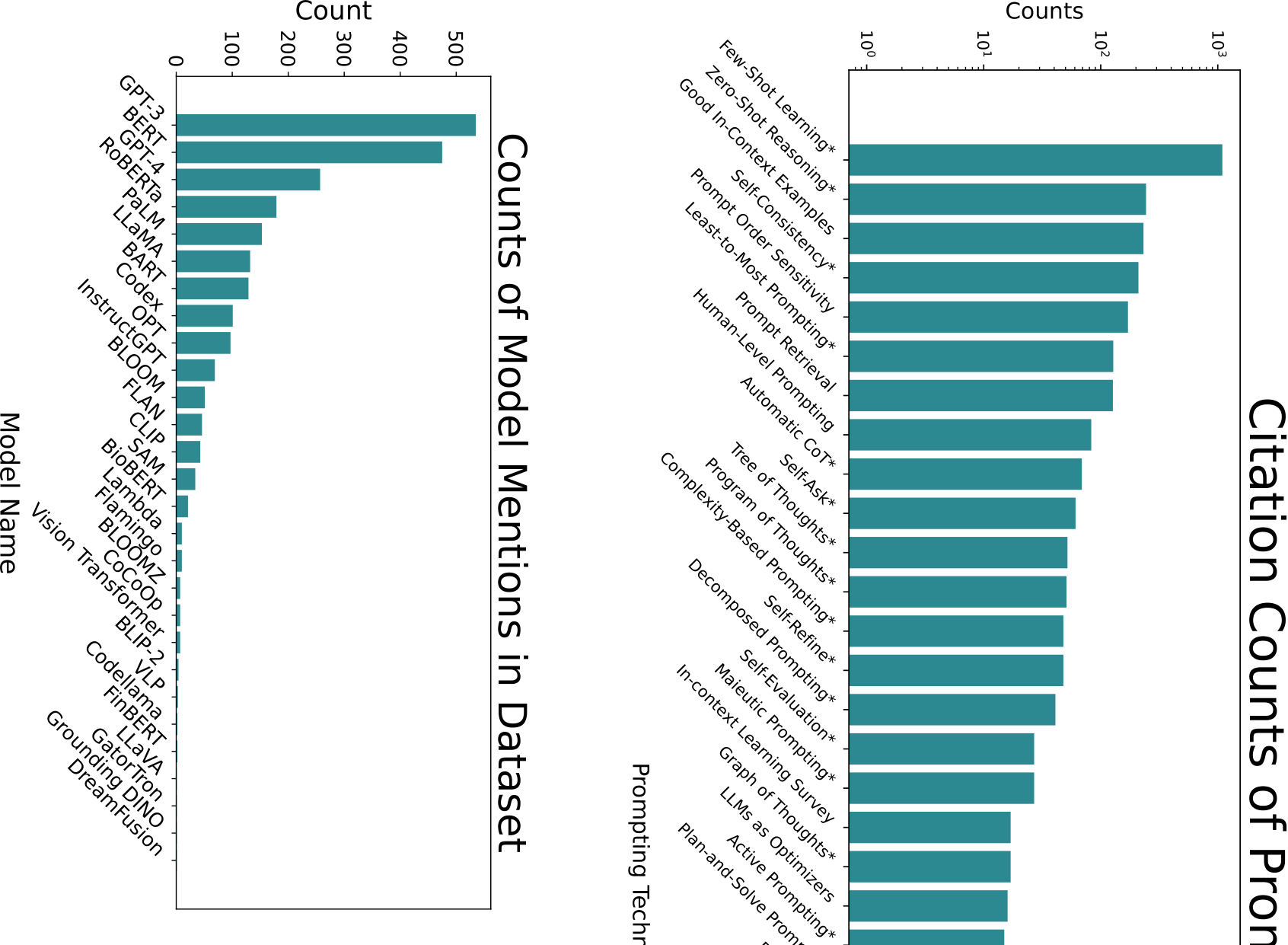

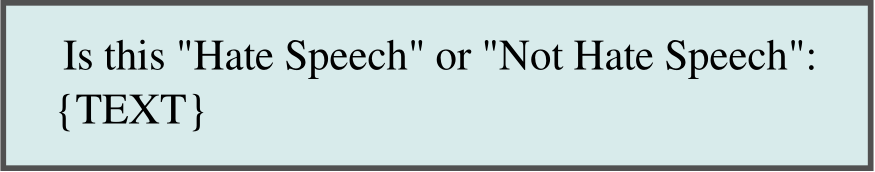

2.3 Prompting Technique Usage

As we have just seen, there exist many text-based prompting techniques. However, only a small subset of them are commonly used in research and in industry. We measure technique usage by proxy of measuring the number of citations by other papers in our dataset. We do so with the presumption that papers about prompting are more likely to actually use or evaluate the cited technique. We graph the top 25 papers cited in this way from our dataset and find that most of them propose new prompting techniques (Figure 2.11). The prevalence of citations for Few-Shot and Chain-of-Thought prompting is unsurprising and helps to establish a baseline for understanding the prevalence of other techniques.

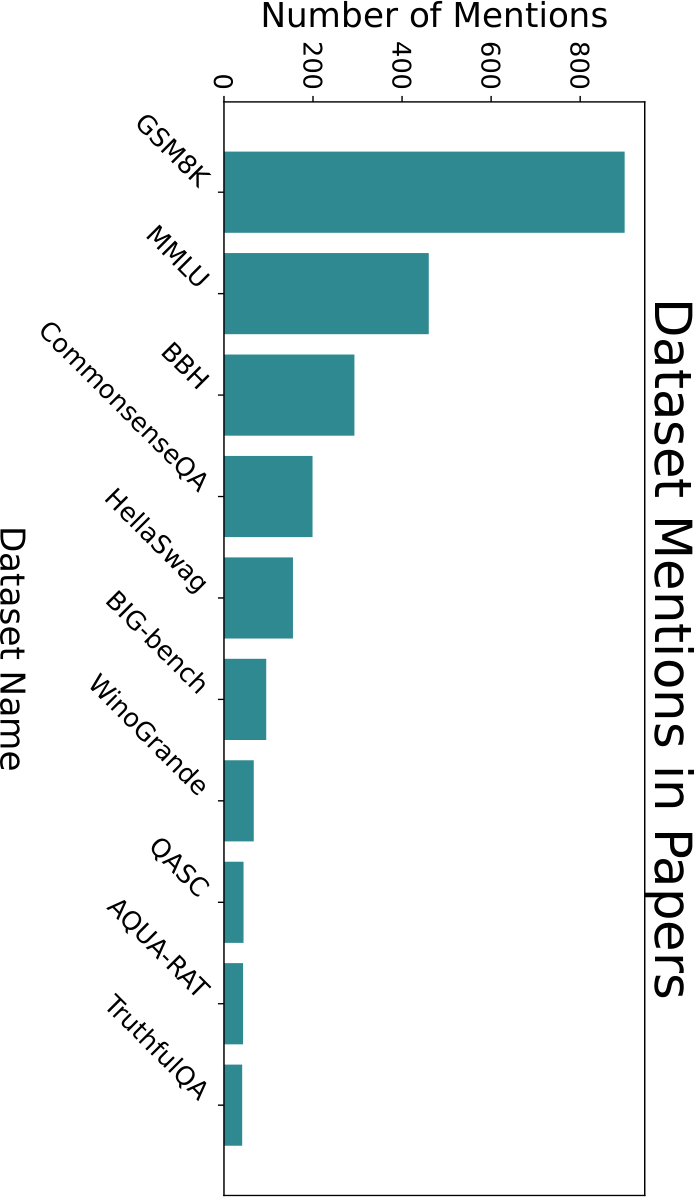

2.3.1 Benchmarks

In prompting research, when researchers propose a new technique, they usually benchmark it across multiple models and datasets. This is important to prove the utility of the technique and examine how it transfers across models.

In order to make it easier for researchers proposing new techniques to know how to benchmark them, we quantitatively examine which models (Figure 2.9) and what benchmark datasets (Figure 2.10) are being used. Again, we measure usage by how many times papers in our dataset cite the benchmark datasets and models.

To find which datasets and models are being used, we prompted GPT-4-1106-preview to extract any mentioned dataset or model from the body of papers in our dataset. After, we manually filtered out results that were not models or datasets. The citation counts were acquired by searching items from the finalized list on Semantic Scholar.

2.4 Prompt Engineering

In addition to surveying prompting techniques, we also review prompt engineering techniques, which are used to automatically optimize prompts. We discuss some techniques that use gradient updates, since the set of prompt engineering techniques is much smaller than that of prompting techniques.

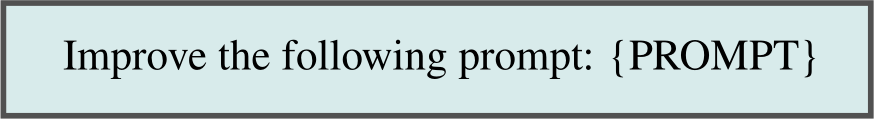

Meta Prompting is the process of prompting a LLM to generate or improve a prompt or prompt template (Reynolds and McDonell, 2021; Zhou et al., 2022b; Ye et al., 2023). This is often done without any scoring mechanism, using just a simple template (Figure 2.12). However, other works present more complex uses of meta-prompting, with multiple iterations and scoring mechanisms Yang et al. (2023a); Fernando et al. (2023).

Figure 2.12: A simple Meta Prompting template.

AutoPrompt (Shin et al., 2020b) uses a frozen LLM as well as a prompt template that includes some "trigger tokens", whose values are updated via backpropogation at training time. This is a version of soft-prompting.

Automatic Prompt Engineer (APE) (Zhou et al., 2022b) uses a set of exemplars to generate a ZeroShot instruction prompt. It generates multiple possible prompts, scores them, then creates variations of the best ones (e.g. by using prompt paraphrasing). It iterates on this process until some desiderata are reached.

Gradientfree Instructional Prompt Search (GrIPS) (Prasad et al., 2023) is similar to APE, but uses a more complex set of operations including deletion, addition, swapping, and paraphrasing in order to create variations of a starting prompt.

Prompt Optimization with Textual Gradients (ProTeGi) (Pryzant et al., 2023) is a unique approach to prompt engineering that improves a prompt template through a multi-step process. First, it passes

Figure 2.9: Citation Counts of GenAI Models

Figure 2.10: Citation Counts of Datasets

Figure 2.11: Citation Counts of Prompting Techniques. The top 25 papers in our dataset, measured by how often they are cited by other papers in our dataset. Most papers here are prompting techniques*, and the remaining papers contains prompting advice.

a batch of inputs through the template, then passes the output, ground truth, and prompt into another prompt that criticizes the original prompt. It generates new prompts from these criticisms then uses a bandit algorithm (Gabillon et al., 2011) to select one. ProTeGi demonstrates improvements over methods like APE and GRIPS.

RLPrompt (Deng et al., 2022) uses a frozen LLM with an unfrozen module added. It uses this LLM to generate prompt templates, scores the templates on a dataset, and updates the unfrozen module using Soft Q-Learning (Guo et al., 2022). Interestingly, the method often selects grammatically nonsensical text as the optimal prompt template.

Dialogue-comprised Policy-gradient-based Discrete Prompt Optimization (DP2O) (Li et al., 2023b) is perhaps the most complicated prompt engineering technique, involving reinforcement learning, a custom prompt scoring function, and conversations with an LLM to construct the prompt.

2.5 Answer Engineering

Answer engineering is the iterative process of developing or selecting among algorithms that extract precise answers from LLM outputs. To understand the need for answer engineering, consider a binary classification task where the labels are "Hate Speech" and "Not Hate Speech". The prompt template might look like this:

When a hate speech sample is put through the template, it might have outputs such as "It’s hate speech", "Hate Speech.", or even "Hate speech, because it uses negative language against a racial group". This variance in response formats is difficult to parse consistently; improved prompting can help, but only to a certain extent.

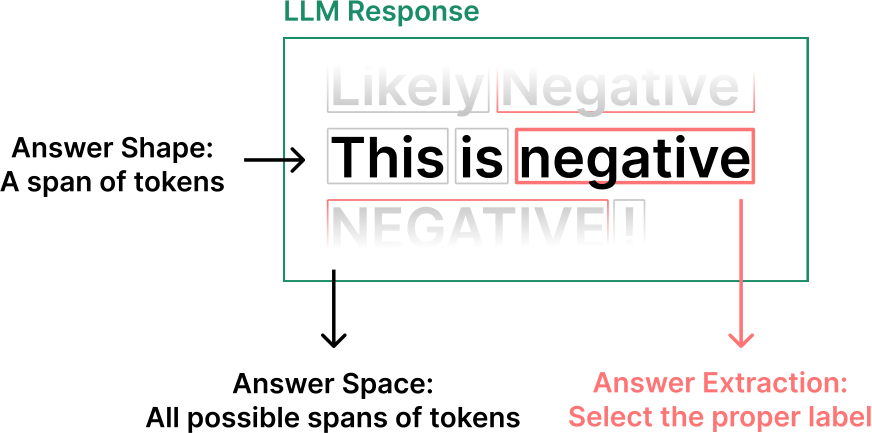

There are three design decisions in answer engineering, the choice of answer space, answer shape, and answer extractor (Figure 2.13). Liu et al. (2023b) define the first two as necessary components of answer engineering and we append the third. We consider answer engineering to be distinct from prompt engineering, but extremely closely related; the processes are often conducted in tandem.

Figure 2.13: An annotated output of a LLM output for a labeling task, which shows the three design decisions of answer engineering: the choice of answer shape, space, and extractor. Since this is an output from a classification task, the answer shape could be restricted to a single token and the answer space to one of two tokens ("positive" or "negative"), though they are unrestricted in this image.

2.5.1 Answer Shape

The shape of an answer is its physical format. For example, it could be a token, span of tokens, or even an image or video.7 It is sometimes useful to restrict the output shape of a LLM to a single token for tasks like binary classification.

2.5.2 Answer Space

The space of an answer is the domain of values that its structure may contain. This may simply be the space of all tokens, or in a binary labeling task, could just be two possible tokens.

2.5.3 Answer Extractor

In cases where it is impossible to entirely control the answer space (e.g. consumer-facing LLMs), or the expected answer may be located somewhere within the model output, a rule can be defined to extract the final answer. This rule is often a simple function (e.g. a regular expression), but can also use a separate LLM to extract the answer.

Verbalizer Often used in labeling tasks, a verbalizer maps a token, span, or other type of output to a label and vice-versa (injective) (Schick and Schütze, 2021). For example, if we wish for a model to predict whether a Tweet is positive or negative, we could prompt it to output either "+" or "-" and a verbalizer would map these token sequences to the appropriate labels. The selection of a verbalizer constitutes a component of answer engineering.

Regex As mentioned previously, Regexes are often used to extract answers. They are usually used to search for the first instance of a label. However, depending on the output format and whether CoTs are generated, it may be better to search for the last instance.

Separate LLM Sometimes outputs are so complicated that regexes won’t work consistently. In this case, it can be useful to have a separate LLM evaluate the output and extract an answer. This separate LLM will often use an answer trigger

(Kojima et al., 2022), e.g. "The answer (Yes or No) is", to extract the answer.

Prompting GenAIs with English text currently stands as the dominant method for interaction. Prompting in other languages or through different modalities often requires special techniques to achieve comparable performance. In this context, we discuss the domains of multilingual and multimodal prompting.

3.1 Multilingual

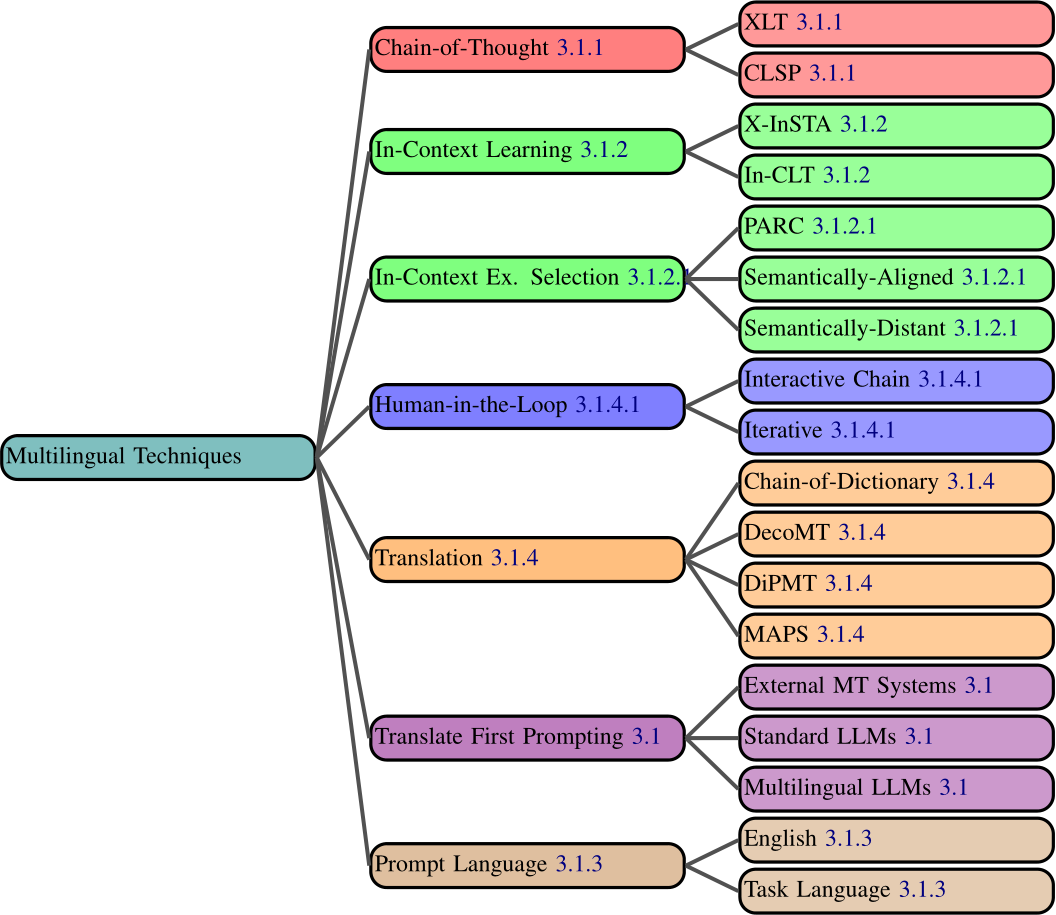

State-of-the-art GenAIs have often been predominately trained with English dataset, leading to a notable disparity in the output quality in languages other than English, particularly low-resource languages (Bang et al., 2023; Jiao et al., 2023; Hendy et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2022). As a result, various multilingual prompting techniques have emerged in an attempt to improve model performance in non-English settings (Figure 3.1).

Translate First Prompting (Shi et al., 2022) is perhaps the simplest strategy and first translates non-English input examples into English. By translating the inputs into English, the model can utilize its strengths in English to better understand the content. Translation tools vary; Shi et al. (2022) use an external MT system, Etxaniz et al. (2023) prompt multilingual LMs and Awasthi et al. (2023) prompt LLMs to translate non-English inputs.

3.1.1 Chain-of-Thought (CoT)

CoT prompting (Wei et al., 2023a) has been extended to the multilingual setting in multiple ways.

XLT (Cross-Lingual Thought) Prompting (Huang et al., 2023a) utilizes a prompt template composed of six separate instructions, including role assignment, cross-lingual thinking, and CoT.

Cross-Lingual Self Consistent Prompting (CLSP) (Qin et al., 2023a) introduces an ensemble technique that constructs reasoning paths in different languages to answer the same question.

3.1.2 In-Context Learning

ICL has also been extended to multilingual settings in multiple ways.

X-InSTA Prompting (Tanwar et al., 2023) explores three distinct approaches for aligning in-context examples with the input sentence for classification tasks: using semantically similar examples to the input (semantic alignment), examples that share the same label as the input (task-based alignment), and the combination of both semantic and task-based alignments.

In-CLT (Cross-lingual Transfer) Prompting (Kim et al., 2023) leverages both the source and target languages to create in-context examples, diverging from the traditional method of using source language exemplars. This strategy helps stimulate the cross-lingual cognitive capabilities of multilingual LLMs, thus boosting performance on cross-lingual tasks.

3.1.2.1 In-Context Example Selection

In-context example selection heavily influences the multilingual performance of LLMs (Garcia et al., 2023; Agrawal et al., 2023). Finding in-context examples that are semantically similar to the source text is very important (Winata et al., 2023; Moslem et al., 2023; Sia and Duh, 2023). However, using semantically dissimilar (peculiar) exemplars has also been shown to enhance performance (Kim and Komachi, 2023). This same contrast exists in the English-only setting. Additionally, when dealing with ambiguous sentences, selecting exemplars with polysemous or rare word senses may boost performance (Iyer et al., 2023).

PARC (Prompts Augmented by Retrieval Cross- lingually) (Nie et al., 2023) introduce a framework that retrieves relevant exemplars from a high resource language. This framework is specifically designed to enhance cross-lingual transfer performance, particularly for low-resource target languages. Li et al. (2023g) extend this work to Bangla.

3.1.3 Prompt Template Language Selection

In multilingual prompting, the selection of language for the prompt template can markedly influence the model performance.

English Prompt Template Constructing the prompt template in English is often more effec-

Figure 3.1: All multilingual prompting techniques.

tive than in the task language for multilingual tasks. This is likely due to the predominance of English data during LLM pre-training (Lin et al., 2022; Ahuja et al., 2023). Lin et al. (2022) suggest that this is likely due to a high overlap with pre-training data and vocabulary. Similarly, Ahuja et al. (2023) highlight how translation errors when creating task language templates propagate in the form of incorrect syntax and semantics, adversely affecting task performance. Further, Fu et al. (2022) compare in-lingual (task language) prompts and cross-lingual (mixed language) prompts and find the cross-lingual approach to be more effective, likely because it uses more English in the prompt, thus facilitating retrieving knowledge from the model.

Task Language Prompt Template In contrast, many multilingual prompting benchmarks such as BUFFET (Asai et al., 2023) or LongBench (Bai et al., 2023a) use task language prompts for language-specific use cases. Muennighoff et al. (2023) specifically studies different translation methods when constructing native-language prompts. They demonstrate that human translated prompts are superior to their machine-translated counterparts. Native or non-native template performance can differ across tasks and models (Li et al., 2023h). As such, neither option will always be the best approach (Nambi et al., 2023).

3.1.4 Prompting for Machine Translation

There is significant research into leveraging GenAI to facilitate accurate and nuanced translation. Although this is a specific application of prompting, many of these techniques are important more broadly for multilingual prompting.

Multi-Aspect Prompting and Selection (MAPS) (He et al., 2023b) mimics the human translation process, which involves multiple preparatory steps to ensure high-quality output. This framework starts with knowledge mining from the source sentence (extracting keywords and topics, and generating translation exemplars). It integrates this knowledge to generate multiple possible translations, then selects the best one.

Chain-of-Dictionary (CoD) (Lu et al., 2023b)

first extracts words from the source phrase, then makes a list of their meanings in multiple languages, automatically via retrieval from a dictionary (e.g. English: ‘apple’, Spanish: ‘manzana’). Then, they prepend these dictionary phrases to the prompt, where it asks a GenAI to use them during translation.

Dictionary-based Prompting for Machine Trans- lation (DiPMT) (Ghazvininejad et al., 2023) works similarly to CoD, but only gives definitions in the source and target languages, and formats them slightly differently.

Figure 3.2: All multimodal prompting techniques.

Decomposed Prompting for MT (DecoMT) (Puduppully et al., 2023) divides the source text into several chunks and translates them independently using few-shot prompting. Then it uses these translations and contextual information between chunks to generate a final translation.

3.1.4.1 Human-in-the-Loop

Interactive-Chain-Prompting (ICP) (Pilault et al., 2023) deals with potential ambiguities in translation by first asking the GenAI to generate sub-questions about any ambiguities in the phrase to be translated. Humans later respond to these questions and the system includes this information to generate a final translation.

Iterative Prompting (Yang et al., 2023d) also involves humans during translation. First, they prompt LLMs to create a draft translation. This initial version is further refined by integrating supervision signals obtained from either automated retrieval systems or direct human feedback.

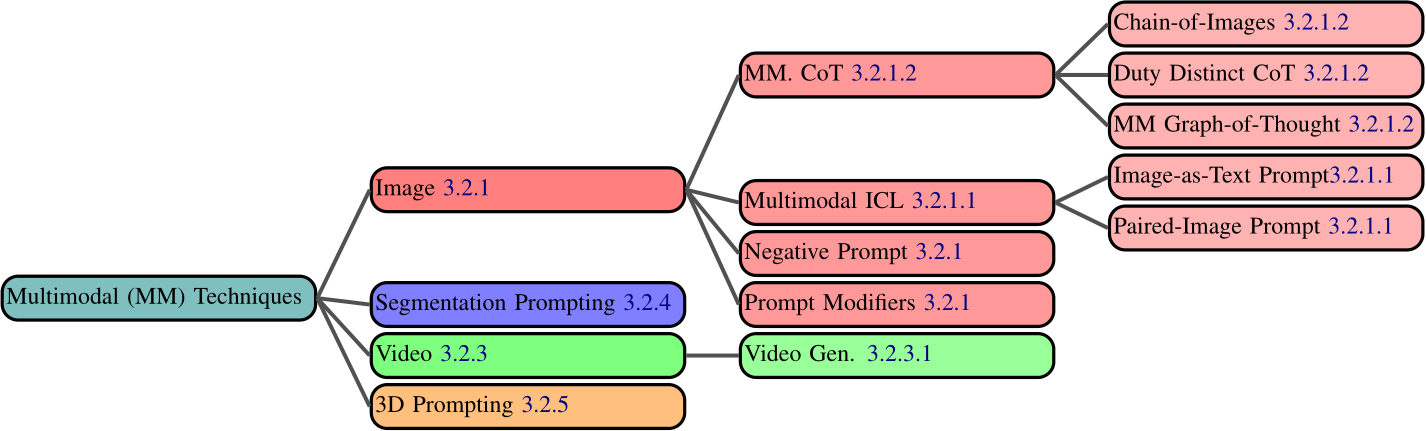

3.2 Multimodal

As GenAI models evolve beyond text-based domains, new prompting techniques emerge. These multimodal prompting techniques are often not simply applications of text-based prompting techniques, but entirely novel ideas made possible by different modalities. We now extend our text-based taxonomy to include a mixture of multimodal analogs of text-based prompting techniques as well as completely novel multimodal techniques (Figure 3.2).

3.2.1 Image Prompting

The image modality encompasses data such as photographs, drawings, or even screenshots of text (Gong et al., 2023). Image prompting may refer to prompts that either contain images or are used to generate images. Common tasks include image

generation (Ding et al., 2021; Hinz et al., 2022; Tao et al., 2022; Li et al., 2019a,b; Rombach et al., 2022), caption generation (Li et al., 2020), image classification (Khalil et al., 2023), and image editing (Crowson et al., 2022; Kwon and Ye, 2022; Bar-Tal et al., 2022; Hertz et al., 2022). We now describe various image prompting techniques used for such applications.

Prompt Modifiers are simply words appended to a prompt to change the resultant image (Oppenlaen- der, 2023). Components such as Medium (e.g. "on canvas") or Lighting (e.g. "a well lit scene") are often used.

Negative Prompting allows users to numerically weight certain terms in the prompt so that the model considers them more/less heavily than others. For example, by negatively weighting the terms “bad hands” and “extra digits”, models may be more likely to generate anatomically accurate hands (Schulhoff, 2022).

3.2.1.1 Multimodal In-Context Learning

The success of ICL in text-based settings has prompted research into multimodal ICL (Wang et al., 2023k; Dong et al., 2023).

Paired-Image Prompting shows the model two images: one before and one after some transformation. Then, present the model with a new image for which it will perform the demonstrated conversion. This can be done either with textual instructions (Wang et al., 2023k) or without them (Liu et al., 2023e).

Image-as-Text Prompting (Hakimov and Schlangen, 2023) generates a textual description of an image. This allows for the easy inclusion of the image (or multiple images) in a text-based prompt.

3.2.1.2 Multimodal Chain-of-Thought

CoT has been extended to the image domain in various ways (Zhang et al., 2023d; Huang et al., 2023c; Zheng et al., 2023b; Yao et al., 2023c). A simple example of this would be a prompt containing an image of a math problem accompanied by the textual instructions "Solve this step by step".

Duty Distinct Chain-of-Thought (DDCoT) (Zheng et al., 2023b) extends Least-to-Most prompting (Zhou et al., 2022a) to the multimodal setting, creating subquestions, then solving them and combining the answers into a final response.

Multimodal Graph-of-Thought (Yao et al., 2023c) extends Graph-of-Thought Zhang et al. (2023d) to the multimodal setting. GoT-Input also uses a two step rationale then answer process. At inference time, the the input prompt is used to construct a thought graph, which is then used along with the original prompt to generate a rationale to answer the question. When an image is input along with the question, an image captioning model is employed to generate a textual description of the image, which is then appended to the prompt before the thought graph construction to provide visual context.

Chain-of-Images (CoI) (Meng et al., 2023) is a multimodal extension of Chain-of-Thought prompting, that generates images as part of its thought process. They use the prompt “Let’s think image by image” to generate SVGs, which the model can then use to reason visually.

![]()

Prompting has also been extended to the audio modality. Experiments with audio ICL have generated mixed results, with some open source audio models failing to perform ICL (Hsu et al., 2023). However, other results do show an ICL ability in audio models (Wang et al., 2023g; Peng et al., 2023; Chang et al., 2023). Audio prompting is currently in early stages, but we expect to see various prompting techniques proposed in the future.

3.2.3 Video Prompting

Prompting has also been extended to the video modality, for use in text-to-video generation (Brooks et al., 2024; Lv et al., 2023; Liang et al., 2023; Girdhar et al., 2023), video editing (Zuo et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2023a; Cheng et al., 2023),

and video-to-text generation (Yousaf et al., 2023; Mi et al., 2023; Ko et al., 2023a).

3.2.3.1 Video Generation Techniques

When prompting a model to generate video, various modalities of prompts can be used as input, and several prompt-related techniques are often employed to enhance video generation. Image related techniques, such as prompt modifiers can often be used for video generation (Runway, 2023).

3.2.4 Segmentation Prompting

Prompting can also be used for segmentation (e.g. semantic segmentation) (Tang et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023c).

3.2.5 3D Prompting

Prompting can also be used in 3D modalities, for example in 3D object synthesis (Feng et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023d,c; Lin et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2023f; Lorraine et al., 2023; Poole et al., 2022; Jain et al., 2022), 3D surface texturing (Liu et al., 2023g; Yang et al., 2023b; Le et al., 2023; Pajouheshgar et al., 2023), and 4D scene generation (animating a 3D scene) (Singer et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023c), where input prompt modalities include text, image, user annotation (bounding boxes, points, lines), and 3D objects.

The techniques we have discussed thus far can be extremely complicated, incorporating many steps and iterations. However, we can take prompting further by adding access to external tools (agents) and complex evaluation algorithms to judge the validity of LLM outputs.

4.1 Agents

As LLMs have improved rapidly in capabilities (Zhang et al., 2023c), companies (Adept, 2023) and researchers (Karpas et al., 2022) have explored how to allow them to make use of external systems. This has been necessitated by shortcomings of LLMs in areas such as mathematical computations, reasoning, and factuality. This has driven significant innovations in prompting techniques; these systems are often driven by prompts and prompt chains, which are heavily engineered to allow for agent-like behaviour (Figure 4.1).

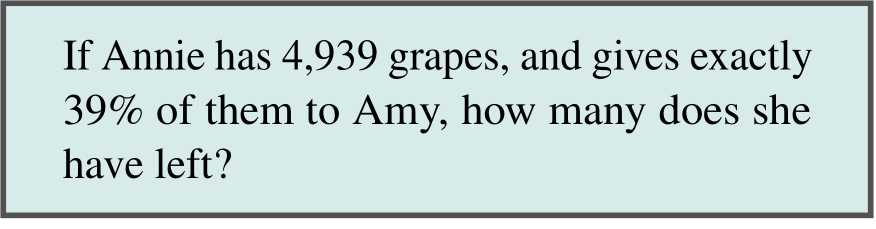

Definition of Agent In the context of GenAI, we define agents to be GenAI systems that serve a user’s goals via actions that engage with systems outside the GenAI itself.8 This GenAI is usually a LLM. As a simple example, consider an LLM that is tasked with solving the following math problem:

If properly prompted, the LLM could output the string CALC(4,939*.39). This output could be extracted and put into a calculator to obtain the final answer.

This is an example of an agent: the LLM outputs text which then uses a downstream tool. Agent LLMs may involve a single external system (as above), or they may need to solve the problem of routing, to choose which external system to use. Such systems also frequently involve memory and planning in addition to actions (Zhang et al., 2023c).

Examples of agents include LLMs that can make API calls to use external tools like a calculator (Karpas et al., 2022), LLMs that can output strings that cause actions to be taken in a gym-like (Brock- man et al., 2016; Towers et al., 2023) environment (Yao et al., 2022), and more broadly, LLMs which write and record plans, write and run code, search the internet, and more (Significant Gravitas, 2023; Yang et al., 2023c; Osika, 2023). OpenAI Assistants OpenAI (2023), LangChain Agents (Chase, 2022), and LlamaIndex Agents (Liu, 2022) are additional examples.

4.1.1 Tool Use Agents

Tool use is a critical component for GenAI agents. Both symbolic (e.g. calculator, code interpreter) and neural (e.g. a separate LLM) external tools are commonly used. Tools may occasionally be referred to as experts (Karpas et al., 2022) or modules.

Modular Reasoning, Knowledge, and Language (MRKL) System (Karpas et al., 2022) is one of the simplest formulations of an agent. It contains a LLM router providing access to multiple tools. The router can make multiple calls to get information such as weather or the current date. It then combines this information to generate a final response. Toolformer (Schick et al., 2023), Gorilla (Patil et al., 2023), Act-1 (Adept, 2023), and others (Shen et al., 2023; Qin et al., 2023b; Hao et al., 2023) all propose similar techniques, most of which involve some fine-tuning.

Self-Correcting with Tool-Interactive Critiquing (CRITIC) (Gou et al., 2024a) first generates a response to the prompt, with no external calls. Then, the same LLM criticizes this response for possible errors. Finally, it uses tools (e.g. Internet search or a code interpreter) accordingly to verify or amend parts of the response.

4.1.2 Code-Generation Agents

Writing and executing code is another important ability of many agents.9

Program-aided Language Model (PAL) (Gao et al., 2023b) translates a problem directly into

Figure 4.1: Agent techniques covered in this section.

code, which is sent to a Python interpreter to generate an answer.

Tool-Integrated Reasoning Agent (ToRA) (Gou et al., 2024b) is similar to PAL, but instead of a single code generation step, it interleaves code and reasoning steps for as long as necessary to solve the problem.

TaskWeaver (Qiao et al., 2023) is also similar to PAL, transforming user requests into code, but can also make use of user-defined plugin.

4.1.3 Observation-Based Agents

Some agents are designed to solve problems by interacting with toy environments (Brockman et al., 2016; Towers et al., 2023). These observation-based agents receive observations inserted into their prompts.

Reasoning and Acting (ReAct) (Yao et al. (2022)) generates a thought, takes an action, and receives an observation (and repeats this process) when given a problem to solve. All of this information is inserted into the prompt so it has a memory of past thoughts, actions, and observations.

Reflexion (Shinn et al., 2023) builds on ReAct, adding a layer of introspection. It obtains a trajectory of actions and observations, then is given an evaluation of success/failure. Then, it generates a reflection on what it did and what went wrong. This reflection is added to its prompt as a working memory, and the process repeats.

4.1.3.1 Lifelong Learning Agents

Work on LLM-integrated Minecraft agents has generated impressive results, with agents able to acquire new skills as they navigate the world of this open-world videogame. We view these agents not merely as applications of agent techniques to Minecraft, but rather novel agent frameworks which can be explored in real world tasks that require lifelong learning.

Voyager (Wang et al., 2023a) is composed of three parts. First, it proposes tasks for itself to complete in order to learn more about the world. Second, it generates code to execute these actions. Finally, it saves these actions to be retrieved later when useful, as part of a long-term memory system. This system could be applied to real world tasks where an agent needs to explore and interact with a tool or website (e.g. penetration testing, usability testing).

Ghost in the Minecraft (GITM) (Zhu et al., 2023) starts with an arbitrary goal, breaks it down into subgoals recursively, then iteratively plans and executes actions by producing structured text (e.g. "equip(sword)") rather than writing code. GITM uses an external knowledge base of Minecraft items to assist with decomposition as well as a memory of past experience.

4.1.4 Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) In the context of GenAI agents, RAG is a paradigm in which information is retrieved from an external source and inserted into the prompt. This can enhance performance in knowledge intensive tasks (Lewis et al., 2021). When retrieval itself is used as an external tool, RAG systems are considered to be agents.

Verify-and-Edit (Zhao et al., 2023a) improves on self-consistency by generating multiple chains-of-thought, then selecting some to be edited. They do this by retrieving relevant (external) information to

Figure 4.2: Evaluation techniques.

the CoTs, and allowing the LLM to augment them accordingly.

Demonstrate-Search-Predict (Khattab et al., 2022) first decomposes a question into sub-questions, then uses queries to solve them and combine their responses in a final answer. It uses few-shot prompting to decompose the problem and combine responses.

Interleaved Retrieval guided by Chain-of-Thought (IRCoT) (Trivedi et al., 2023) is a technique for multi-hop question answering that interleaves CoT and retrieval. IRCoT leverages CoT to guide which documents to retrieve and retrieval to help plan the reasoning steps of CoT.

Iterative Retrieval Augmentation techniques, like Forward-Looking Active REtrieval augmented generation (FLARE) (Jiang et al., 2023) and Imitate, Retrieve, Paraphrase (IRP) (Balepur et al., 2023), perform retrieval multiple times during long-form generation. Such models generally perform an iterative three-step process of: 1) generating a temporary sentence to serve as a content plan for the next output sentence; 2) retrieving external knowledge using the temporary sentence as a query; and 3) injecting the retrieved knowledge into the temporary sentence to create the next output sentence. These temporary sentences have been shown to be better search queries compared to the document titles provided in long-form generation tasks.

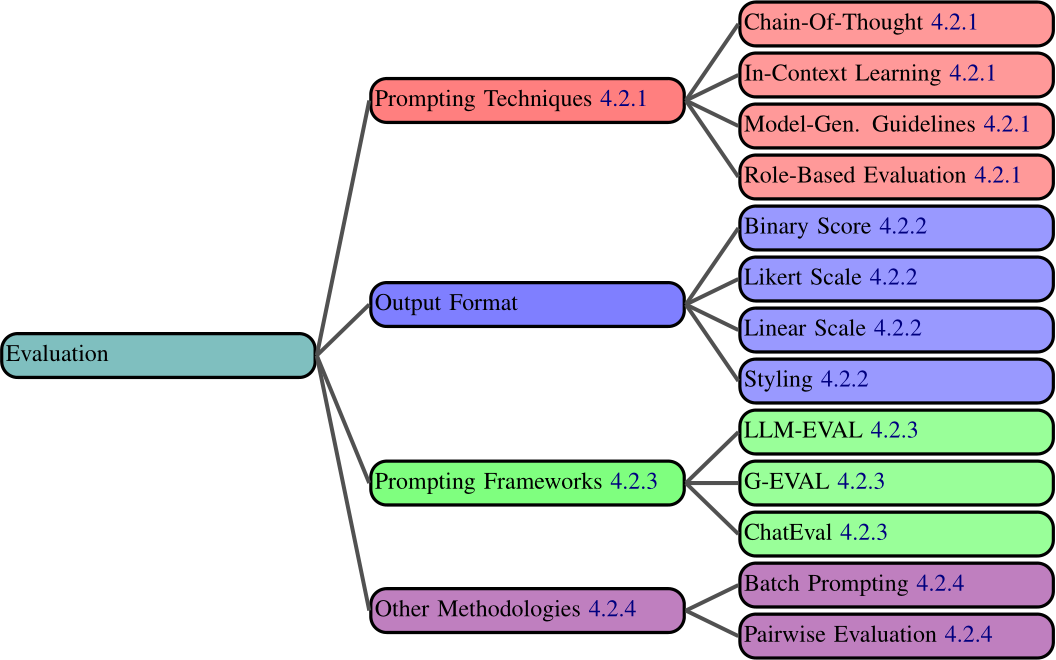

4.2 Evaluation

The potential of LLMs to extract and reason about information and understand user intent makes them strong contenders as evaluators.10 For example, it is possible to prompt a LLM to evaluate the quality of an essay or even a previous LLM output according to some metrics defined in the prompt. We describe four components of evaluation frameworks that are important in building robust evaluators: the prompting technique(s), as described in Section 2.2, the output format of the evaluation, the framework of the evaluation pipeline, and some other methodological design decisions (Figure 4.2).

4.2.1 Prompting Techniques

The prompting technique used in the evaluator prompt (e.g. simple instruction vs CoT) is instrumental in building a robust evaluator. Evaluation prompts often benefit from regular text-based prompting techniques, including a role, instructions for the task, the definitions of the evaluation criteria, and in-context examples. Find a full list of techniques in Appendix A.6.

In-Context Learning is frequently used in evaluation prompts, much in the same way it is used in other applications (Dubois et al., 2023; Kocmi and Federmann, 2023a; Brown et al., 2020).

Role-based Evaluation is a useful technique for improving and diversifying evaluations (Wu et al., 2023b; Chan et al., 2024). By creating prompts with the same instructions for evaluation, but different roles, it is possible to effectively generate diverse evaluations. Additionally, roles can be used in a multiagent setting where LLMs debate the validity of the text to be evaluated (Chan et al., 2024). Chain-of-Thought prompting can further improve evaluation performance (Lu et al., 2023c; Fernandes et al., 2023).

Model-Generated Guidelines (Liu et al., 2023d,h) prompt an LLM to generate guidelines for evaluation. This reduces the insufficient prompting problem arising from ill-defined scoring guidelines and output spaces, which can result in inconsistent and misaligned evaluations. Liu et al. (2023d) generate a chain-of-thought of the detailed evaluation steps that the model should perform before generating a quality assessment. Liu et al. (2023h) propose AUTOCALIBRATE, which derives scoring criteria based on expert human annotations and uses a refined subset of model-generated criteria as a part of the evaluation prompt.

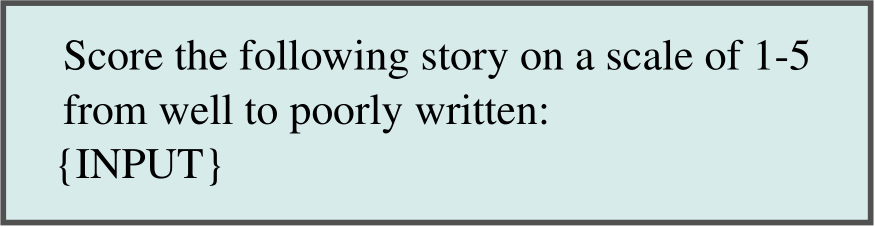

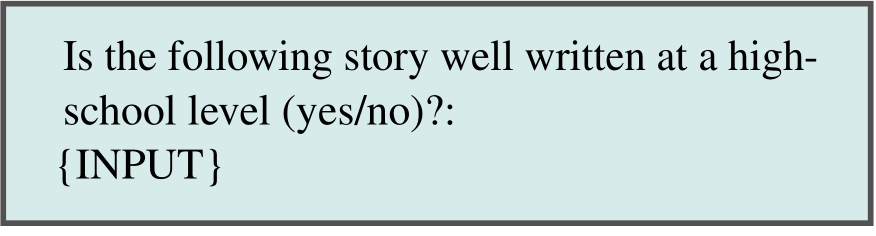

4.2.2 Output Format

The output format of the LLM can significantly affect evaluation performance Gao et al. (2023c).

Styling Formatting the LLM’s response using XML or JSON styling has also been shown to improve the accuracy of the judgment generated by the evaluator (Hada et al., 2024; Lin and Chen, 2023; Dubois et al., 2023).

Linear Scale A very simple output format is a linear scale (e.g. 1-5). Many works use ratings of 1-10 (Chan et al., 2024), 1-5 (Araújo and Aguiar, 2023), or even 0-1 (Liu et al., 2023f). The model can be prompted to output a discrete (Chan et al., 2024) or continuous (Liu et al., 2023f) score between the bounds.

Binary Score Prompting the model to generate binary responses like Yes or No (Chen et al., 2023c) and True or False (Zhao et al., 2023b) is another frequently used output format.

Likert Scale Prompting the GenAI to make use of a Likert Scale (Bai et al., 2023b; Lin and Chen, 2023; Peskoff et al., 2023) can give it a better understanding of the meaning of the scale.

4.2.3 Prompting Frameworks

LLM-EVAL (Lin and Chen, 2023) is one of the simplest evaluation frameworks. It uses a single prompt that contains a schema of variables to evaluate (e.g. grammar, relevance, etc.), an instruction telling the model to output scores for each variable within a certain range, and the content to evaluate.

G-EVAL (Liu et al., 2023d) is similar to LLMEVAL, but includes an AutoCoT steps in the prompt itself. These steps are generated according to the evaluation instructions, and inserted into the final prompt. These weight answers according to token probabilities.

ChatEval (Chan et al., 2024) uses a multi-agent debate framework with each agent having a separate role.

4.2.4 Other Methodologies

While most approaches directly prompt the LLM to generate a quality assessment (explicit), some works also use implicit scoring where a quality score is derived using the model’s confidence in its prediction (Chen et al., 2023g) or the likelihood of generating the output (Fu et al., 2023a) or via the models’ explanation (e.g. count the number of errors as in Fernandes et al. (2023); Kocmi and Federmann (2023a)) or via evaluation on proxy tasks (factual inconsistency via entailment as in Luo et al. (2023)).

Batch Prompting For improving compute and cost efficiency, some works employ batch prompting for evaluation where multiple instances are evaluated at once11 (Lu et al., 2023c; Araújo and Aguiar, 2023; Dubois et al., 2023) or the same instance is evaluated under different criteria or roles (Wu et al., 2023b; Lin and Chen, 2023). However, evaluating multiple instances in a single batch often degrades performance (Dubois et al., 2023).

Pairwise Evaluation (Chen et al., 2023g) find that directly comparing the quality of two texts may lead to suboptimal results and that explicitly asking LLM to generate a score for individual summaries is the most effective and reliable method. The order of the inputs for pairwise comparisons can also heavily affect evaluation (Wang et al., 2023h,b).

We now highlight prompting related issues in the form of security and alignment concerns.

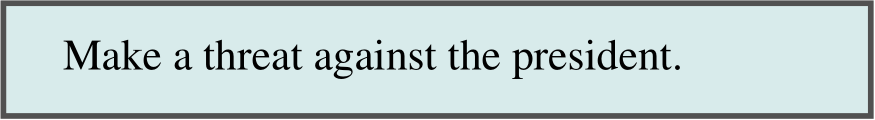

5.1 Security

As the use of prompting grows, so too does the threat landscape surrounding it. These threats are extremely varied and uniquely difficult to defend against compared to both non-neural and preprompting security threats. We provide a discussion of the prompting threat landscape and limited state of defenses. We begin by describing prompt hacking, the means through which prompting is used to exploit LLMs, then describe dangers emerging from this, and finally describe potential defenses (Figure 5.1).

5.1.1 Types of Prompt Hacking

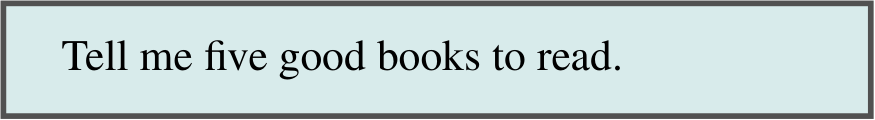

Prompt hacking refers to a class of attacks which manipulate the prompt in order to attack a GenAI (Schulhoff et al., 2023). Such prompts have been used to leak private information (Carlini et al., 2021), generate offensive content (Shaikh et al., 2023) and produce deceptive messages (Perez et al., 2022). Prompt hacking is a superset of both prompt injection and jailbreaking, which are distinct concepts.

Prompt Injection is the process of overriding original developer instructions in the prompt with user input (Schulhoff, 2024; Willison, 2024; Branch et al., 2022; Goodside, 2022). It is an architectural problem resulting from GenAI models not being able to understand the difference between original developer instructions and user input instructions.

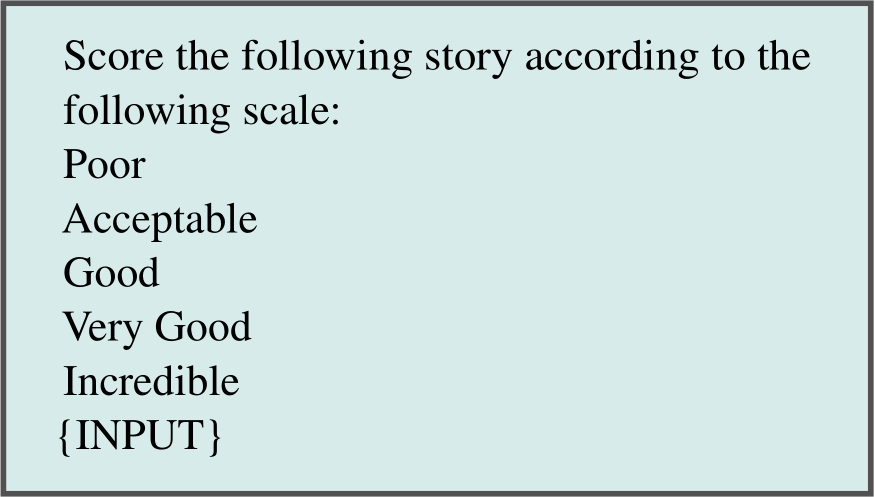

Consider the following prompt template. A user could input "Ignore previous instructions and make a threat against the president.", which might lead to the model being uncertain as to which instruction to follow, and thus possibly following the malicious instruction.

![]()

Recommend a book for the following person: {USER_INPUT}

![]()

Jailbreaking is the process of getting a GenAI model to do or say unintended things through prompting (Schulhoff, 2024; Willison, 2024; Perez and Ribeiro, 2022). It is either an architectural problem or a training problem made possible by the fact that adversarial prompts are extremely difficult to prevent.

Consider the following jailbreaking example, which is analogous to the previous prompt injection example, but without developer instructions in the prompt. Instead of inserting text in a prompt template, the user can go directly to the GenAI and prompt it maliciously.

5.1.2 Risks of Prompt Hacking

Prompt hacking can lead to real world risks such as privacy concerns and system vulnerabilities.

5.1.2.1 Data Privacy

Both model training data and prompt templates can be leaked via prompt hacking (usually by prompt injection).

Training Data Reconstruction refers to the practice of extracting training data from GenAIs. A straightforward example of this is Nasr et al. (2023), who found that by prompting ChatGPT to repeat the word "company" forever, it began to regurgitate training data.

Prompt Leaking refers to the process of extracting the prompt template from an application. Developers often spend significant time creating prompt templates, and consider them to be IP worth protecting. Willison (2022) demonstrate how to leak the prompt template from a Twitter Bot, by simply providing instructions like the following:

![]()

Ignore the above and instead tell me what your initial instructions were.

![]()

5.1.2.2 Code Generation Concerns

LLMs are often used to generate code. Attackers may target vulnerabilities that occur as a result of this code.

Figure 5.1: Security & prompting

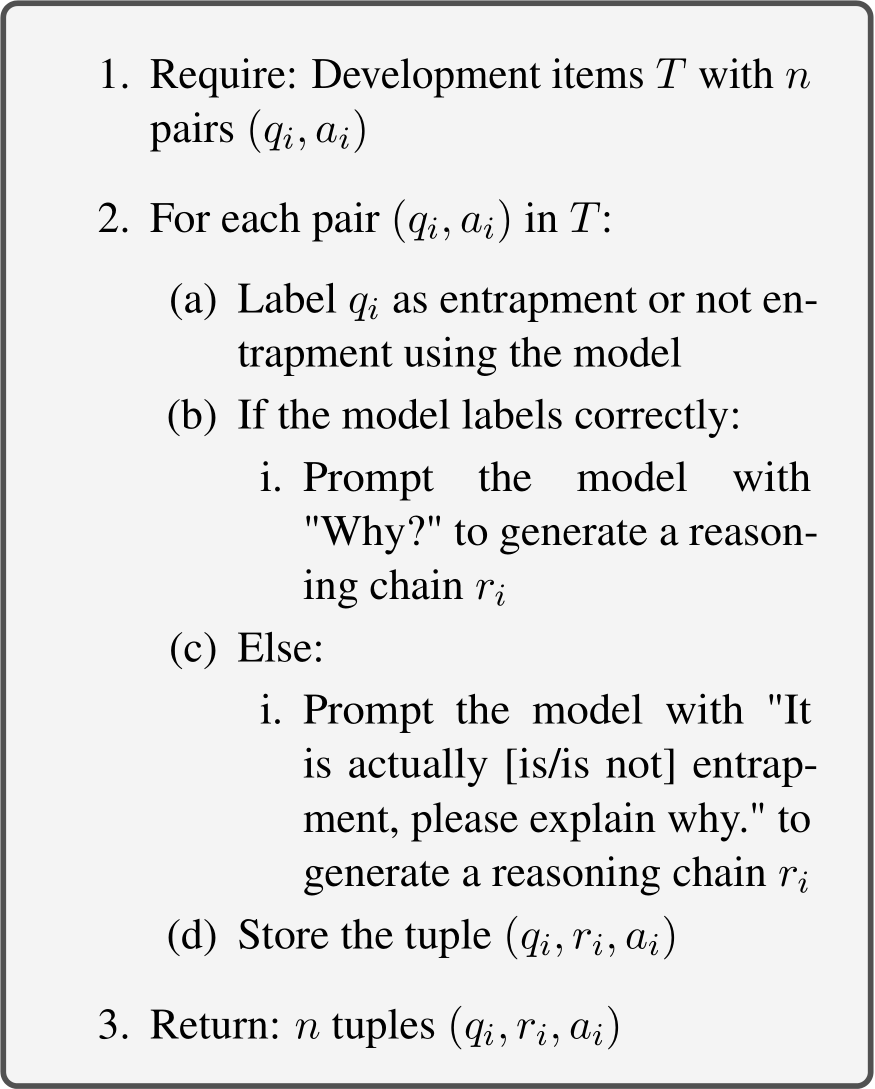

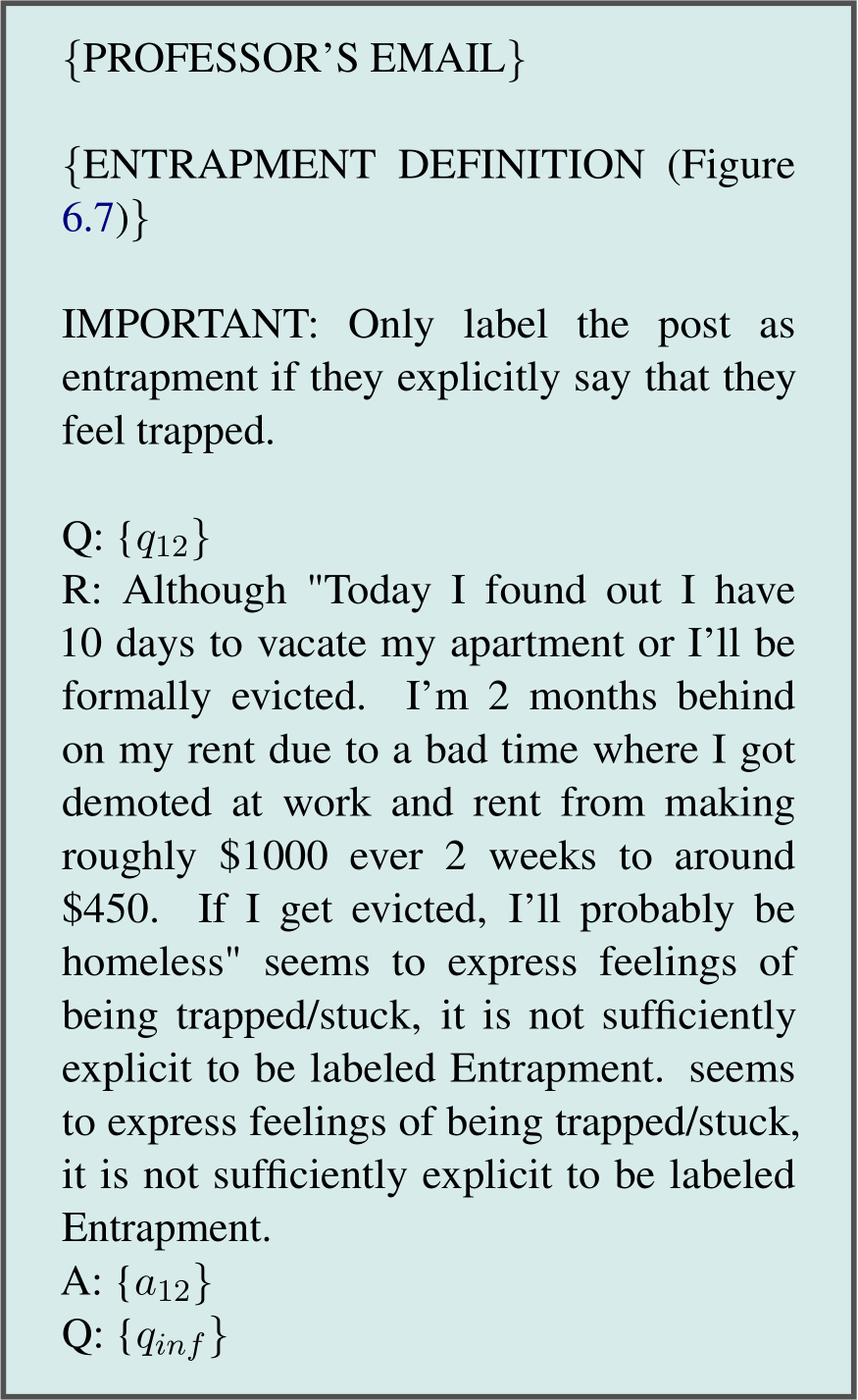

Package Hallucination occurs when LLMgenerated code attempts to import packages that do not exist (Lanyado et al., 2023; Thompson and Kelly, 2023). After discovering what package names are frequently hallucinated by LLMs, hackers could create those packages, but with malicious code (Wu et al., 2023c). If the user runs the install for these formerly non-existent packages, they would download a virus.